Central Asia

| Central Asia | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) | |

| Area | 4,003,451 km2 (1,545,741 sq mi)[lower-alpha 1] |

| Population | 67,986,864 |

| Density | 16.6/km2 (43/sq mi) |

| Countries |

Kazakhstan Kyrgyzstan Tajikistan Turkmenistan Uzbekistan |

| Regional Center | Kazakhstan |

| Nominal GDP (2012) | $295.331 billion |

| GDP per capita (2012) | $6,044 |

Central Asia or Middle Asia is the core region of the Asian continent and stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to China in the east and from Afghanistan in the south to Russia in the north. It is also sometimes referred to as Middle Asia, and, colloquially, "the 'stans" (as the six countries generally considered to be within the region all have names ending with the Persian suffix "-stan", meaning "land of")[1] and is within the scope of the wider Eurasian continent.

In modern contexts, all definitions of Central Asia include these five republics of the former Soviet Union: Kazakhstan (pop. 17 million), Kyrgyzstan (5.7 million), Tajikistan (8.0 million), Turkmenistan (5.2 million), and Uzbekistan (30 million), for a total population of about 66 million as of 2013–2014. Afghanistan (pop. 31.1 million) is also sometimes included.

Various definitions of Central Asia's exact composition exist, and not one definition is universally accepted. Despite this uncertainty in defining borders, the region does have some important overall characteristics. For one, Central Asia has historically been closely tied to its nomadic peoples and the Silk Road.[2] As a result, it has acted as a crossroads for the movement of people, goods, and ideas between Europe, Western Asia, South Asia, and East Asia.[3]

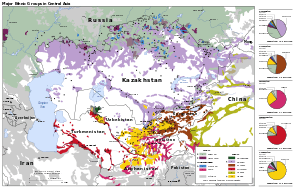

During pre-Islamic and early Islamic times, Central Asia was a predominantly Iranian[4][5] region that included the sedentary Eastern Iranian-speaking Bactrians, Sogdians and Chorasmians, and the semi-nomadic Scythians and Parthians. The ancient sedentary population played an important role in the history of Central Asia. After expansion by Turkic peoples, Central Asia also became the homeland for many Turkic peoples, including the Kazakhs, Uzbeks, Turkmen, Kyrgyz, Uyghurs, and other extinct Turkic nations; Turkic languages largely replaced the Iranian languages spoken in the area. Central Asia is sometimes referred to as Turkestan.[6][7][8]

Since the earliest of times, Central Asia has been a crossroads between different civilizations. The Silk Road connected Muslim lands with the people of Europe, India, and China.[9] This crossroads position has intensified the conflict between tribalism and traditionalism and modernization.[10]

From the mid-19th century, up to the end of the 20th century, most of Central Asia was part of the Russian Empire and later the Soviet Union, both being Slavic-majority countries. As of 2011, the five "'stans'" are still home to about 7 million Russians and 500,000 Ukrainians.[11][12][13]

Definitions

The idea of Central Asia as a distinct region of the world was introduced in 1843 by the geographer Alexander von Humboldt. The borders of Central Asia are subject to multiple definitions. Historically built political geography and geoculture are two significant parameters widely used in the scholarly literature about the definitions of the Central Asia.[14]

The most limited definition was the official one of the Soviet Union, which defined Middle Asia as consisting solely of Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. This definition was also often used outside the USSR during this period.

However, the Russian culture has two distinct terms: Средняя Азия (Srednyaya Aziya or "Middle Asia", the narrower definition, which includes only those traditionally non-Slavic, Central Asian lands that were incorporated within those borders of historical Russia) and Центральная Азия (Centralïnaya Aziya or "Central Asia", the wider definition, which includes Central Asian lands that have never been part of historical Russia).

Soon after independence, the leaders of the four former Soviet Central Asian Republics met in Tashkent and declared that the definition of Central Asia should include Kazakhstan as well as the original four included by the Soviets. Since then, this has become the most common definition of Central Asia.

The UNESCO general history of Central Asia, written just before the collapse of the USSR, defines the region based on climate and uses far larger borders. According to it, Central Asia includes Mongolia, Tibet, northeast Iran (Golestan, North Khorasan and Razavi provinces), central-east Russia south of the Taiga, large parts of China, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the former Central Asian Soviet republics (the five "Stans" of the former Soviet Union).

An alternative method is to define the region based on ethnicity, and in particular, areas populated by Eastern Turkic, Eastern Iranian, or Mongolian peoples. These areas include Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, the Turkic regions of southern Siberia, the five republics, and Afghan Turkestan. Afghanistan as a whole, the northern and western areas of Pakistan and the Kashmir Valley of India may also be included. The Tibetans and Ladakhi are also included. Insofar, most of the mentioned peoples are considered the "indigenous" peoples of the vast region.

There are several places that claim to be the geographic center of Asia, for example Kyzyl, the capital of Tuva in the Russian Federation, and a village 200 miles (320 km) north of Ürümqi, the capital of the Xinjiang region of China.[15]

Geography

.jpg)

Central Asia is an extremely large region of varied geography, including high passes and mountains (Tian Shan), vast deserts (Kyzyl Kum, Taklamakan), and especially treeless, grassy steppes. The vast steppe areas of Central Asia are considered together with the steppes of Eastern Europe as a homogeneous geographical zone known as the Eurasian Steppe.

Much of the land of Central Asia is too dry or too rugged for farming. The Gobi desert extends from the foot of the Pamirs, 77° E, to the Great Khingan (Da Hinggan) Mountains, 116°–118° E.

Central Asia has the following geographic extremes:

- The world's northernmost desert (sand dunes), at Buurug Deliin Els, Mongolia, 50°18′ N.

- The Northern Hemisphere's southernmost permafrost, at Erdenetsogt sum, Mongolia, 46°17′ N.

- The world's shortest distance between non-frozen desert and permafrost: 770 km (480 mi).

- The Eurasian pole of inaccessibility.

A majority of the people earn a living by herding livestock. Industrial activity centers in the region's cities.

Major rivers of the region include the Amu Darya, the Syr Darya, Irtysh, the Hari River and the Murghab River. Major bodies of water include the Aral Sea and Lake Balkhash, both of which are part of the huge west-central Asian endorheic basin that also includes the Caspian Sea.

Both of these bodies of water have shrunk significantly in recent decades due to diversion of water from rivers that feed them for irrigation and industrial purposes. Water is an extremely valuable resource in arid Central Asia and can lead to rather significant international disputes.

Divisions

The northern belt is part of the Eurasian Steppe. In the northwest, north of the Caspian Sea, Central Asia merges into the Russian Steppe. To the northeast, Dzungaria and the Tarim Basin may sometimes be included in Central Asia. Just west of Dzungaria, Zhetysu, or Semirechye, is south of Lake Balkhash and north of the Tian Shan Mountains. Khorezm is south of the Aral Sea along the Amu Darya. Southeast of the Aral Sea, Maveranahr is between the Amu Darya and Syr Darya. Transoxiana is the land north of the middle and upper Amu Darya (Oxus). Bactria included northern Afghanistan and the upper Amu Darya. Sogdiana was north of Bactria and included the trading cities of Bukhara and Samarkhand. Khorasan and Margiana approximate northeastern Iran. The Kyzyl Kum Desert is northeast of the Amu Darya, and the Karakum Desert southwest of it.

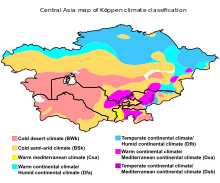

Climate

Because Central Asia is not buffered by a large body of water, temperature fluctuations are more severe. In most of the places the climate is moderate.

According to the WWF Ecozones system, Central Asia is part of the Palearctic ecozone. The largest biomes in Central Asia are the temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands biome. Central Asia also contains the montane grasslands and shrublands, deserts and xeric shrublands as well as temperate coniferous forests biomes.

History

Although, during the golden age of Orientalism the place of Central Asia in the world history was marginalized, contemporary historiography has rediscovered the "centrality" of the Central Asia.[16] The history of Central Asia is defined by the area's climate and geography. The aridness of the region made agriculture difficult, and its distance from the sea cut it off from much trade. Thus, few major cities developed in the region; instead, the area was for millennia dominated by the nomadic horse peoples of the steppe.

Relations between the steppe nomads and the settled people in and around Central Asia were long marked by conflict. The nomadic lifestyle was well suited to warfare, and the steppe horse riders became some of the most militarily potent people in the world, limited only by their lack of internal unity. Any internal unity that was achieved was most probably due to the influence of the Silk Road, which traveled along Central Asia. Periodically, great leaders or changing conditions would organize several tribes into one force and create an almost unstoppable power. These included the Hun invasion of Europe, the Wu Hu attacks on China and most notably the Mongol conquest of much of Eurasia.[17]

During pre-Islamic and early Islamic times, southern Central Asia was inhabited predominantly by speakers of Iranian languages.[4][18] Among the ancient sedentary Iranian peoples, the Sogdians and Chorasmians played an important role, while Iranian peoples such as Scythians and the later on Alans lived a nomadic or semi-nomadic lifestyle. The well-preserved Tarim mummies with Caucasoid features have been found in the Tarim Basin.[19]

The main migration of Turkic peoples occurred between the 5th and 10th centuries, when they spread across most of Central Asia. The Tang Chinese were defeated by the Arabs at the battle of Talas in 751, marking the end of the Tang Dynasty's western expansion. The Tibetan Empire would take the chance to rule portion of Central Asia along with South Asia. During the 13th and 14th centuries, the Mongols conquered and ruled the largest contiguous empire in recorded history. Most of Central Asia fell under the control of the Chagatai Khanate.

The dominance of the nomads ended in the 16th century, as firearms allowed settled peoples to gain control of the region. Russia, China, and other powers expanded into the region and had captured the bulk of Central Asia by the end of the 19th century. After the Russian Revolution, the western Central Asian regions were incorporated into the Soviet Union. The eastern part of Central Asia, known as East Turkistan or Xinjiang, was incorporated into the People's Republic of China. Mongolia remained independent but became a Soviet satellite state. Afghanistan remained relatively independent of major influence by the USSR until the Saur Revolution of 1978.

The Soviet areas of Central Asia saw much industrialization and construction of infrastructure, but also the suppression of local cultures, hundreds of thousands of deaths from failed collectivization programs, and a lasting legacy of ethnic tensions and environmental problems. Soviet authorities deported millions of people, including entire nationalities,[20] from western areas of the USSR to Central Asia and Siberia.[21] According to Touraj Atabaki and Sanjyot Mehendale, "From 1959 to 1970, about two million people from various parts of the Soviet Union migrated to Central Asia, of which about one million moved to Kazakhstan."[22]

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, five countries gained independence. In nearly all the new states, former Communist Party officials retained power as local strongmen. None of the new republics could be considered functional democracies in the early days of independence, although in recent years Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and Mongolia have made further progress towards more open societies, unlike Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan, which have maintained many Soviet-style repressive tactics.[23]

Culture

Religions

Islam is the religion most common in the Central Asian Republics, Afghanistan, Xinjiang and the peripheral western regions, such as Bashkortostan. Most Central Asian Muslims are Sunni, although there are sizable Shia minorities in Afghanistan and Tajikistan.

Buddhism and Zoroastrianism were the major faiths in Central Asia prior to the arrival of Islam. Zoroastrian influence is still felt today in such celebrations as Nowruz, held in all five of the Central Asian states.

Buddhism was a prominent religion in Central Asia prior to the arrival of Islam, and the transmission of Buddhism along the Silk Road eventually brought the religion to China. Amongst the Turkic peoples, Tengrianism was the popular religion before arrival of Islam. Tibetan Buddhism is most common in Tibet, Mongolia, Ladakh and the southern Russian regions of Siberia.

The form of Christianity most practiced in the region in previous centuries was Nestorianism, but now the largest denomination is the Russian Orthodox Church, with many members in Kazakhstan.

The Bukharan Jews were once a sizable community in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, but nearly all have emigrated since the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

In Siberia, Shamanism is practiced, including forms of divination, such as Kumalak.

Contact and migration with Han people from China has brought Confucianism, Daoism, Mahayana Buddhism, and other Chinese folk beliefs into the region.

Arts

At the crossroads of Asia, shamanistic practices live alongside Buddhism. Thus, Yama, Lord of Death, was revered in Tibet as a spiritual guardian and judge. Mongolian Buddhism, in particular, was influenced by Tibetan Buddhism. The Qianlong Emperor of Qing China in the 18th century was Tibetan Buddhist and would sometimes travel from Beijing to other cities for personal religious worship.

Central Asia also has an indigenous form of improvisational oral poetry that is over 1000 years old. It is principally practiced in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan by akyns, lyrical improvisationists. They engage in lyrical battles, the aitysh or the alym sabak. The tradition arose out of early bardic oral historians. They are usually accompanied by a stringed instrument—in Kyrgyzstan, a three-stringed komuz, and in Kazakhstan, a similar two-stringed instrument, the dombra.

Photography in Central Asia began to develop after 1882, when a Russian Mennonite photographer named Wilhelm Penner moved to the Khanate of Khiva during the Mennonite migration to Central Asia led by Claas Epp, Jr.. Upon his arrival to Khanate of Khiva, Penner shared his photography skills with a local student Khudaybergen Divanov, who later became the founder of Uzbek photography.[24]

Some also learn to sing the Manas, Kyrgyzstan's epic poem (those who learn the Manas exclusively but do not improvise are called manaschis). During Soviet rule, akyn performance was co-opted by the authorities and subsequently declined in popularity. With the fall of the Soviet Union, it has enjoyed a resurgence, although akyns still do use their art to campaign for political candidates. A 2005 The Washington Post article proposed a similarity between the improvisational art of akyns and modern freestyle rap performed in the West.[25]

As a consequence of Russian colonization, European fine arts – painting, sculpture and graphics – have developed in Central Asia. The first years of the Soviet regime saw the appearance of modernism, which took inspiration from the Russian avant-garde movement. Until the 1980s, Central Asian arts had developed along with general tendencies of Soviet arts. In the 90's, arts of the region underwent some significant changes. Institutionally speaking, some fields of arts were regulated by the birth of the art market, some stayed as representatives of official views, while many were sponsored by international organizations. The years of 1990 – 2000 were times for the establishment of contemporary arts. In the region, many important international exhibitions are taking place, Central Asian art is represented in European and American museums, and the Central Asian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale has been organized since 2005.

Sports

Equestrian sports are traditional in Central Asia, with disciplines like endurance riding, buzkashi, dzhigit and kyz kuu.

Association football is popular across Central Asia. Most countries are members of the Central Asian Football Association, a region of the Asian Football Confederation. However, Kazakhstan is a member of the UEFA.

Wrestling is popular across Central Asia, with Kazakhstan having claimed 14 Olympic medals and Uzbekistan seven. As former Soviet states, Central Asian countries have been successful in gymnastics.

Cricket is the most popular sport in Afghanistan. The Afghanistan national cricket team, first formed in 2001, has claimed wins over Bangladesh, West Indies and Zimbabwe.

Notable Kazakh competitors include cyclists Alexander Vinokourov and Andrey Kashechkin, boxer Vassiliy Jirov, runner Olga Shishigina, decathlete Dmitriy Karpov, gymnast Aliya Yussupova, judoka Askhat Zhitkeyev and Maxim Rakov, skier Vladimir Smirnov, weightlifter Ilya Ilyin, and figure skater Denis Ten.

Notable Uzbekistani competitors include cyclist Djamolidine Abdoujaparov, boxer Ruslan Chagaev, canoer Michael Kolganov, gymnast Oksana Chusovitina, tennis player Denis Istomin and chess player Rustam Kasimdzhanov.

Territory and region data

| Country | Area km² |

Population (2016)[26][27][28][29][30] |

Population density per km2 |

Nominal GDP millions of USD (2015) |

GDP per capita in USD (IMF 2015)[31] |

HDI (2015) | Capital | Official languages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

2,724,900 | 17,067,216 | 6.3 | 216,036 | 9,796 | 0.788 | Astana | Kazakh, Russian |

| |

199,950 | 5,940,743 | 29.7 | 7,402 | 1,113 | 0.655 | Bishkek | Kyrgyz, Russian |

| |

142,550 | 8,628,742 | 60.4 | 9,242 | 922 | 0.624 | Dushanbe | Tajik, Russian |

| |

488,100 | 5,417,285 | 11.1 | 47,932 | 6,622 | 0.688 | Ashgabat | Turkmen |

| |

447,400 | 30,932,878 | 69.1 | 62,613 | 2,121 | 0.675 | Tashkent | Uzbek |

Demographics

By a broad definition including Mongolia and Afghanistan, more than 90 million people live in Central Asia, about 2% of Asia's total population. Of the regions of Asia, only North Asia has fewer people. It has a population density of 9 people per km2, vastly less than the 80.5 people per km2 of the continent as a whole.

Languages

Russian, as well as being spoken by around six million ethnic Russians and Ukrainians of Central Asia,[32] is the de facto lingua franca throughout the former Soviet Central Asian Republics. Mandarin Chinese has an equally dominant presence in Inner Mongolia, Qinghai and Xinjiang.

The languages of the majority of the inhabitants of the former Soviet Central Asian Republics come from the Turkic language group.[33] Turkmen, is mainly spoken in Turkmenistan, and as a minority language in Afghanistan, Russia, Iran and Turkey. Kazakh and Kyrgyz are related languages of the Kypchak group of Turkic languages and are spoken throughout Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and as a minority language in Tajikistan, Afghanistan and Xinjiang. Uzbek and Uyghur are spoken in Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Afghanistan and Xinjiang.

The Turkic languages may belong to a larger, but controversial, Altaic language family, which includes Mongolian. Mongolian is spoken throughout Mongolia and into Buryatia, Kalmyk, Tuva, Inner Mongolia, and Xinjiang.

Middle Iranian languages were once spoken throughout Central Asia, such as the once prominent Sogdian, Khwarezmian, Bactrian and Scythian, which are now extinct and belonged to the Eastern Iranian family. The Eastern Iranian Pashto language is still spoken in Afghanistan and northwestern Pakistan. Other minor Eastern Iranian languages such as Shughni, Munji, Ishkashimi, Sarikoli, Wakhi, Yaghnobi and Ossetic are also spoken at various places in Central Asia. Varieties of Persian are also spoken as a major language in the region, locally known as Dari (in Afghanistan), Tajik (in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan), and Bukhori (by the Bukharan Jews of Central Asia).

Tocharian, another Indo-European language group, which was once predominant in oases on the northern edge of the Tarim Basin of Xinjiang, is now extinct.

Other language groups include the Tibetic languages, spoken by around six million people across the Tibetan Plateau and into Qinghai, Sichuan, Ladakh and Baltistan, and the Nuristani languages of northeastern Afghanistan. Dardic languages, such as Shina, Kashmiri, Pashayi and Khowar, are also spoken in eastern Afghanistan, the Gilgit-Baltistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa of Pakistan and the disputed territory of Kashmir.

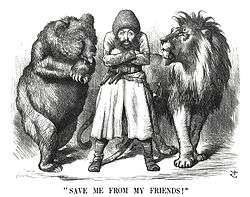

Geostrategy

Central Asia has long been a strategic location merely because of its proximity to several great powers on the Eurasian landmass. The region itself never held a dominant stationary population nor was able to make use of natural resources. Thus, it has rarely throughout history become the seat of power for an empire or influential state. Central Asia has been divided, redivided, conquered out of existence, and fragmented time and time again. Central Asia has served more as the battleground for outside powers than as a power in its own right.

Central Asia had both the advantage and disadvantage of a central location between four historical seats of power. From its central location, it has access to trade routes to and from all the regional powers. On the other hand, it has been continuously vulnerable to attack from all sides throughout its history, resulting in political fragmentation or outright power vacuum, as it is successively dominated.

- To the North, the steppe allowed for rapid mobility, first for nomadic horseback warriors like the Huns and Mongols, and later for Russian traders, eventually supported by railroads. As the Russian Empire expanded to the East, it would also push down into Central Asia towards the sea, in a search for warm water ports. The Soviet bloc would reinforce dominance from the North and attempt to project power as far south as Afghanistan.

- To the East, the demographic and cultural weight of Chinese empires continually pushed outward into Central Asia since the Silk road period of Han Dynasty. However, with the Sino-Soviet split and collapse of Soviet Union, China would project its soft power into Central Asia, most notably in the case of Afghanistan, to counter Russian dominance of the region.

- To the Southeast, the demographic and cultural influence of India was felt in Central Asia, notably in Tibet, the Hindu Kush, and slightly beyond. From its base in India, the British Empire competed with the Russian Empire for influence in the region in the 19th and 20th centuries.

- To the Southwest, Western Asian powers have expanded into the southern areas of Central Asia (usually Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, and Turkmenistan). Several Persian empires would conquer and reconquer parts of Central Asia; Alexander the Great's Hellenic empire would extend into Central Asia; two Islamic empires would exert substantial influence throughout the region; and the modern state of Iran has projected influence throughout the region as well. Turkey, through a common Turkic nation identity, has gradually increased its ties and influence as well in the region. Furthermore, all Central Asian Turkic-speaking states are together with Turkey part of the Turkic Council.

In the post–Cold War era, Central Asia is an ethnic cauldron, prone to instability and conflicts, without a sense of national identity, but rather a mess of historical cultural influences, tribal and clan loyalties, and religious fervor. Projecting influence into the area is no longer just Russia, but also Turkey, Iran, China, Pakistan, India and the United States:

- Russia continues to dominate political decision-making throughout the former SSRs; although, as other countries move into the area, Russia's influence has begun to wane though Russia still maintains military bases in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan.[35]

- The United States, with its military involvement in the region and oil diplomacy, is also significantly involved in the region's politics. The United States and other NATO members are the main contributors to the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan and also exert considerable influence in other Central Asian nations.

- China has security ties with Central Asian states through the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, and conducts energy trade bilaterally.[36]

- India has geographic proximity to the Central Asian region and, in addition, enjoys considerable influence on Afghanistan.[37][38] India maintains a military base at Farkhor, Tajikistan, and also has extensive military relations with Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.[39]

- Turkey also exerts considerable influence in the region on account of its ethnic and linguistic ties with the Turkic peoples of Central Asia and its involvement in the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline. Political and economic relations are growing rapidly (e.g., Turkey recently eliminated visa requirements for citizens of the Central Asian Turkic republics).

- Iran, the seat of historical empires that controlled parts of Central Asia, has historical and cultural links to the region and is vying to construct an oil pipeline from the Caspian Sea to the Persian Gulf.

- Pakistan, a nuclear-armed Islamic state, has a history of political relations with neighboring Afghanistan and is termed capable of exercising influence. For some Central Asian nations, the shortest route to the ocean lies through Pakistan. Pakistan seeks natural gas from Central Asia and supports the development of pipelines from its countries. According to an independent study, Turkmenistan is supposed to be the fifth largest natural gas field in the world.[40] The mountain ranges and areas in northern Pakistan lie on the fringes of greater Central Asia; the Gilgit–Baltistan region of Pakistan lies adjacent to Tajikistan, separated only by the narrow Afghan Wakhan Corridor. Being located on the northwest of South Asia, the area forming modern-day Pakistan maintained extensive historical and cultural links with the central Asian region.

Russian historian Lev Gumilev wrote that Xiongnu, Mongols (Mongol Empire, Zunghar Khanate) and Turkic peoples (Turkic Khaganate, Uyghur Khaganate) played a role to stop Chinese aggression to the north. The Turkic Khaganate had special policy against Chinese assimilation policy.[41] Another interesting theoretical analysis on the historical-geopolitics of the Central Asia was made through the reinterpretation of Orkhun Inscripts.[42]

The region, along with Russia, is also part of "the great pivot" as per the Heartland Theory of Halford Mackinder, which says that the power which controls Central Asia—richly endowed with natural resources—shall ultimately be the "empire of the world".[43]

War on Terror

In the context of the United States' War on Terror, Central Asia has once again become the center of geostrategic calculations. Pakistan's status has been upgraded by the U.S. government to Major non-NATO ally because of its central role in serving as a staging point for the invasion of Afghanistan, providing intelligence on Al-Qaeda operations in the region, and leading the hunt on Osama bin Laden.

Afghanistan, which had served as a haven and source of support for Al-Qaeda under the protection of Mullah Omar and the Taliban, was the target of a U.S. invasion in 2001 and ongoing reconstruction and drug-eradication efforts. U.S. military bases have also been established in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, causing both Russia and the People's Republic of China to voice their concern over a permanent U.S. military presence in the region.

Western governments have accused Russia, China and the former Soviet republics of justifying the suppression of separatist movements, and the associated ethnics and religion with the War on Terror.

Major cultural and economic centers

Cities within the regular definition of Central Asia and Afghanistan

| City | Country | Population | Image | Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Astana | |

835,153 (2014) |

|

The capital and second largest city in Kazakhstan. After Kazakhstan gained its independence in 1991, the city and the region were renamed Aqmola. The name was often translated as "White Tombstone", but actually means "Holy Place" or "Holy Shrine". The "White Tombstone" literal translation was too appropriate for many visitors to escape notice in almost all guide books and travel accounts. In 1994, the city was designated as the future capital of the newly independent country and again renamed to the present Astana after the capital was officially moved from Almaty in 1997. |

| Almaty | |

1,552,349 (2015) |

|

It was the capital of Kazakhstan (and its predecessor, the Kazakh SSR) from 1929 to 1998. Despite losing its status as the capital, Almaty remains the major commercial center of Kazakhstan. It is a recognized financial center of Kazakhstan and the Central Asian region. |

| Bishkek | |

865,527 (2009) |

|

The capital and the largest city of Kyrgyzstan. Bishkek is also the administrative center of Chuy Region, which surrounds the city, even though the city itself is not part of the region, but rather a region-level unit of Kyrgyzstan. |

| Osh | |

243,216 (2009) |

|

The second largest city of Kyrgyzstan. Osh is also the administrative center of Osh Region, which surrounds the city, even though the city itself is not part of the region, but rather a region-level unit of Kyrgyzstan. |

| Dushanbe | |

780,000 (2014) |

|

The capital and largest city of Tajikistan. Dushanbe means "Monday" in Tajik and Persian,[44] and the name reflects the fact that the city grew on the site of a village that originally was a popular Monday marketplace. |

| Ashgabat | |

909,000 (2009) |

|

The capital and largest city of Turkmenistan. Ashgabat is a relatively young city, growing out of a village of the same name established by Russians in 1818. It is not far from the site of Nisa, the ancient capital of the Parthians, and it grew on the ruins of the Silk Road city of Konjikala, which was first mentioned as a wine-producing village in the 2nd century BCE and was leveled by an earthquake in the 1st century BCE (a precursor of the 1948 Ashgabat earthquake). Konjikala was rebuilt because of its advantageous location on the Silk Road, and it flourished until its destruction by Mongols in the 13th century CE. After that, it survived as a small village until the Russians took over in the 19th century.[45][46] |

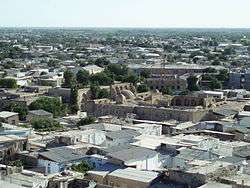

| Bukhara | |

237,900 (1999) |

|

The nation's fifth-largest city and the capital of the Bukhara Region of Uzbekistan. Bukhara has been one of the main centers of Persian civilization from its early days in the 6th century BCE, and, since the 12th century CE, Turkic speakers gradually moved in. Its architecture and archaeological sites form one of the pillars of Central Asian history and art. |

| Kokand | |

209,389 (2011) |

|

Kokand (Uzbek: Qo‘qon / Қўқон; Tajik: Хӯқанд; Persian: خوقند; Chagatai: خوقند; Russian: Коканд) is a city in Fergana Region in eastern Uzbekistan, at the southwestern edge of the Fergana Valley. It has a population of 192,500 (1999 census estimate). Kokand is 228 km southeast of Tashkent, 115 km west of Andijan, and 88 km west of Fergana. It is nicknamed "City of Winds", or sometimes "Town of the Boar". |

| Samarkand | |

596,300 (2008) |

|

The second largest city in Uzbekistan and the capital of Samarqand Region. The city is most noted for its central position on the Silk Road between China and the West, and for being an Islamic center for scholarly study. |

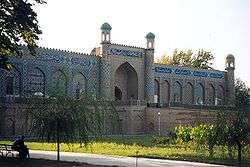

| Tashkent | |

2,180,000 (2008) |

|

The capital and largest city of Uzbekistan. In pre-Islamic and early Islamic times, the town and the region were known as Chach. Tashkent started as an oasis on the Chirchik River, near the foothills of the Golestan Mountains. In ancient times, this area contained Beitian, probably the summer "capital" of the Kangju confederacy.[47] |

| Kabul | |

3,895,000 (2011) |

|

The capital and largest city of Afghanistan. The city of Kabul is thought to have been established between 2000 BCE and 1500 BCE.[48] In the Rig Veda (composed between 1700–1100 BCE), the word Kubhā is mentioned, which appears to refer to the Kabul River.[49] |

| Mazar-e Sharif | |

375,181 (2008) |

|

The fourth largest city in Afghanistan and the capital of Balkh province, is linked by roads to Kabul in the southeast, Herat to the west and Uzbekistan to the north. |

See also

- Chinese Central Asia: Western Regions and Xinjiang

- Central Asian studies

- Central Asian Union

- Central Asian Football Federation

- Continental pole of inaccessibility

- Economic Cooperation Organization

- Inner Asia

- Hindutash

- University of Central Asia

- Central Asians in Ancient Indian literature

- India’s ‘Connect Central Asia’ Policy

- Turkestan

Notes

- ↑ The area figure is based on the combined areas of five countries in Central Asia.

References

- ↑ Paul McFedries (25 October 2001). "stans". Word Spy. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- ↑ Steppe Nomads and Central Asia Archived 29 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Silkroad Foundation, Adela C.Y. Lee. "Travelers on the Silk Road". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- 1 2 Encyclopædia Iranica, "CENTRAL ASIA: The Islamic period up to the Mongols", C. Edmund Bosworth: "In early Islamic times Persians tended to identify all the lands to the northeast of Khorasan and lying beyond the Oxus with the region of Turan, which in the Shahnama of Ferdowsi is regarded as the land allotted to Fereydun's son Tur. The denizens of Turan were held to include the Turks, in the first four centuries of Islam essentially those nomadizing beyond the Jaxartes, and behind them the Chinese (see Kowalski; Minorsky, "Turan"). Turan thus became both an ethnic and a diareeah term, but always containing ambiguities and contradictions, arising from the fact that all through Islamic times the lands immediately beyond the Oxus and along its lower reaches were the homes not of Turks but of Iranian peoples, such as the Sogdians and Khwarezmians."

- ↑ C.E. Bosworth, "The Appearance of the Arabs in Central Asia under the Umayyads and the establishment of Islam", in History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. IV: The Age of Achievement: AD 750 to the End of the Fifteenth Century, Part One: The Historical, Social and Economic Setting, edited by M. S. Asimov and C. E. Bosworth. Multiple History Series. Paris: Motilal Banarsidass Publ./UNESCO Publishing, 1999. excerpt from page 23: "Central Asia in the early seventh century, was ethnically, still largely an Iranian land whose people used various Middle Iranian languages.".

- ↑ Polo, Marco; Smethurst, Paul (2005). The Travels of Marco Polo. p. 676. ISBN 978-0-7607-6589-0.

- ↑ Ferrand, Gabriel (1913), "Ibn Batūtā", Relations de voyages et textes géographiques arabes, persans et turks relatifs à l'Extrème-Orient du 8e au 18e siècles (Volumes 1 and 2) (in French), Paris: Ernest Laroux, pp. 426–458

- ↑ Andrea, Bernadette. "Ibn Fadlan's Journey to Russia: A Tenth‐Century Traveler from Baghdad to the Volga River by Richard N. Frye: Review by Bernadette Andrea". Middle East Studies Association Bulletin. 41 (2): 201–202.

- ↑ Ta'lim Primary 6 Parent and Teacher Guide (p.72) – Islamic Publications Limited for the Institute of Ismaili Studies London

- ↑ Phillips, Andrew; James, Paul (2013). "National Identity between Tradition and Reflexive Modernisation: The Contradictions of Central Asia". National Identities. 3 (1): 23–35.

In Central Asia the collision of modernity and tradition led all but the most deracinated of the intellectuals-clerics to seek salvation in reconstituted variants of traditional identities rather than succumb to the modern European idea of nationalism. The inability of the elites to form a united front, as demonstrated in the numerous declarations of autonomy by different authorities during the Russian civil war, paved the way for the Soviet re-conquest of Central Asia in the early 1920s.

- ↑ Демоскоп Weekly – Приложение. Справочник статистических показателей Archived 16 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine.. Demoscope.ru. Retrieved on 29 July 2013.

- ↑ "5.01.00.03 Национальный состав населения" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-06.

- ↑ Итоги переписи населения Таджикистана 2000 года: национальный, возрастной, половой, семейный и образовательный составы Archived 25 August 2011 at WebCite. Demoscope.ru (20 January 2000). Retrieved on 2013-07-29.

- ↑ Mehmet Akif Okur, "Classical Texts Of the Geopolitics and the "Heart Of Eurasia", Journal of Turkish World Studies, XIV/2, pp.74–75 http://tdid.ege.edu.tr/files/dergi_14_2/mehmet_akif_okur.pdf https://www.academia.edu/10035574/CLASSICAL_TEXTS_OF_THE_GEOPOLITICS_AND_THE_HEART_OF_EURASIA_Jeopoliti%C4%9Fin_Klasik_Metinleri_ve_Avrasya_n%C4%B1n_Kalbi_

- ↑ 43°40'52"N 87°19'52"E Degree Confluence Project.

- ↑ Mehmet Akif Okur, "Classical Texts Of the Geopolitics and the "Heart Of Eurasia", Journal of Turkish World Studies, XIV/2, pp.86–90 https://www.academia.edu/10035574/CLASSICAL_TEXTS_OF_THE_GEOPOLITICS_AND_THE_HEART_OF_EURASIA_Jeopoliti%C4%9Fin_Klasik_Metinleri_ve_Avrasya_n%C4%B1n_Kalbi_ http://tdid.ege.edu.tr/files/dergi_14_2/mehmet_akif_okur.pdf

- ↑ A Land Conquered by the Mongols

- ↑ C.E. Bosworth, "The Appearance of the Arabs in Central Asia under the Umayyads and the establishment of Islam", in History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. IV: The Age of Achievement: AD 750 to the End of the Fifteenth Century, Part One: The Historical, Social and Economic Setting, edited by M. S. Asimov and C. E. Bosworth. Multiple History Series. Paris: UNESCO Publishing, 1998. excerpt from page 23: "Central Asia in the early seventh century, was ethnically, still largely an Iranian land whose people used various Middle Iranian languages.

- ↑ Saiget, Robert J. (19 April 2005). "Caucasians preceded East Asians in basin". The Washington Times. News World Communications. Archived from the original on 20 April 2005. Retrieved 20 August 2007.

A study last year by Jilin University also found that the mummies' DNA had Europoid genes.

- ↑ "Deported Nationalities". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ Anne Applebaum – Gulag: A History Intro

- ↑ "Central Asia and the Caucasus: transnationalism and diaspora". Touraj Atabaki, Sanjyot Mehendale (2005). p.66. ISBN 0-415-33260-5

- ↑ "Democracy Index 2011". Economist Intelligence Unit.

- ↑ Walter Ratliff, "Pilgrims on the Silk Road: A Muslim-Christian Encounter in Khiva", Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2010

- ↑ ""In Central Asia, a Revival of an Ancient Form of Rap – Art of Ad-Libbing Oral History Draws New Devotees in Post-Communist Era" by Peter Finn, Washington Post Foreign Service, Sunday, March 6, 2005, p. A20.". The Washington Post. 6 March 2005. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ "The World Factbook". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ "The World Factbook". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ "The World Factbook". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ "The World Factbook". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ "The World Factbook". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ "IMF World Economic Outlook (WEO) – Recovery Strengthens, Remains Uneven, April 2014". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ Robert Greenall, Russians left behind in Central Asia, BBC News, 23 November 2005.

- ↑ "Ethnographic maps". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ Millward, James A. (2007), Eurasian crossroads: a history of Xinjiang, Columbia University Press, pp. 45–47, ISBN 0-231-13924-1

- ↑ "Why Russia Will Send More Troops to Central Asia". Stratfor. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ Scheineson, Andrew (24 March 2009). "The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation". Backgrounder. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- ↑ "India: Afghanistan's influential ally". BBC News. 8 October 2009. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ "India, Pakistan and the Battle for Afghanistan". TIME.com. 5 December 2009. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ Reiter, Erich; Hazdra, Peter (2004). The Impact of Asian Powers on Global Developments. Springer, 2004. ISBN 978-3-7908-0092-0.

- ↑ Chazan, Guy. "Turkmenistan Gas Field Is One of World's Largest". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ ЛЮДИ И ПРИРОДА ВЕЛИКОЙ СТЕПИ (Russian)

- ↑ Mehmet Akif Okur, "Classical Texts Of the Geopolitics and the "Heart Of Eurasia", Journal of Turkish World Studies, XIV/2, pp.91–100 https://www.academia.edu/10035574/CLASSICAL_TEXTS_OF_THE_GEOPOLITICS_AND_THE_HEART_OF_EURASIA_Jeopoliti%C4%9Fin_Klasik_Metinleri_ve_Avrasya_n%C4%B1n_Kalbi_ http://tdid.ege.edu.tr/files/dergi_14_2/mehmet_akif_okur.pdf

- ↑ For an analysis of Mackinder's approach from the perspective of "Critical Geopolitics" look: Mehmet Akif Okur, "Classical Texts Of the Geopolitics and the "Heart Of Eurasia", Journal of Turkish World Studies, XIV/2, pp.76–80 https://www.academia.edu/10035574/CLASSICAL_TEXTS_OF_THE_GEOPOLITICS_AND_THE_HEART_OF_EURASIA_Jeopoliti%C4%9Fin_Klasik_Metinleri_ve_Avrasya_n%C4%B1n_Kalbi_ http://tdid.ege.edu.tr/files/dergi_14_2/mehmet_akif_okur.pdf

- ↑ D. Saimaddinov, S. D. Kholmatova, and S. Karimov, Tajik-Russian Dictionary, Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Tajikistan, Rudaki Institute of Language and Literature, Scientific Center for Persian-Tajik Culture, Dushanbe, 2006.

- ↑ Konjikala Archived 29 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine.: the Silk Road precursor of Ashgabat

- ↑ Konjikala, in: MaryLee Knowlton, Turkmenistan, Marshall Cavendish, 2006, pp. 40–41, ISBN 0-7614-2014-2, ISBN 978-0-7614-2014-9 (viewable on Google Books).

- ↑ Pulleyblank, Edwin G (1963). "The consonantal system of Old Chinese". Asia Major. 9: 94.

- ↑ The history of Afghanistan, Ghandara.com website

- ↑ "Kabul" Chambers's Encyclopaedia: A Dictionary of Universal Knowledge (1901 edition) J.B. Lippincott Company, NY, page 385. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

Further reading

- Blank, Stephen J. (2013). Central Asia After 2014. ISBN 978-1-58487-593-2.

- Chow, Edward. "Central Asia's Pipelines: Field of Dreams and Reality", in Pipeline Politics in Asia: The Intersection of Demand, Energy Markets, and Supply Routes. National Bureau of Asian Research, 2010.

- Farah, Paolo Davide, Energy Security, Water Resources and Economic Development in Central Asia, World Scientific Reference on Globalisation in Eurasia and the Pacific Rim, Imperial College Press (London, UK) & World Scientific Publishing, Nov. 2015.. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2701215

- Dani, A.H. and V.M. Masson, eds. History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Paris: UNESCO, 1992.* Gorshunova. Olga V. Svjashennye derevja Khodzhi Barora..., ( Sacred Trees of Khodzhi Baror: Phytolatry and the Cult of Female Deity in Central Asia) in Etnoragraficheskoe Obozrenie, 2008, n° 1, pp. 71–82. ISSN 0869-5415. (Russian).

- Klein, I.; Gessner, U.; Kuenzer. "Regional land cover mapping and change detection in Central Asia using MODIS time-series". Applied Geography. 35 (1–2): 219–234. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2012.06.016.

- Mandelbaum, Michael, ed. Central Asia and the World: Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Turkmenistan. New York: Council on Foreign Relations Press, 1994.

- Marcinkowski, M. Ismail. Persian Historiography and Geography: Bertold Spuler on Major Works Produced in Iran, the Caucasus, Central Asia, Pakistan and Early Ottoman Turkey. Singapore: Pustaka Nasional, 2003.

- Olcott, Martha Brill. Central Asia's New States: Independence, Foreign policy, and Regional security. Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace Press, 1996.

- Phillips, Andrew; James, Paul (2013). "National Identity between Tradition and Reflexive Modernisation: The Contradictions of Central Asia". National Identities. 3 (1): 23–35.

- Hasan Bulent Paksoy. ALPAMYSH: Central Asian Identity under Russian Rule. Hartford: AACAR, 1989. http://vlib.iue.it/carrie/texts/carrie_books/paksoy-1/

- Soucek, Svatopluk. A History of Inner Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Rall, Ted. Silk Road to Ruin: Is Central Asia the New Middle East? New York: NBM Publishing, 2006.

- Stone, L.A. The International Politics of Central Eurasia (272 pp). Central Eurasian Studies On Line: Accessible via the Web Page of the International Eurasian Institute for Economic and Political Research: http://www.iicas.org/forumen.htm

- Weston, David. Teaching about Inner Asia, Bloomington, Indiana: ERIC Clearinghouse for Social Studies, 1989.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Central Asia. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Central Asia. |

- The Library: Central on politics, universities, culture, languages, etc.

- Central Asian Gateway Project of UNDP and CER, managed by N. Talibdjanov (since 2003).

- Modernity, State and Society in Central Asia: A Research Guide

- General Map of Central Asia: I is a historic map from 1874

- Archive of Turkish Oral Narrative, Texas Tech University; literature, customs, full-text works