Krishna

| Krishna | |

|---|---|

| Divine, Love, Knowledge, Beauty | |

|

Krishna statute at the Sri Mariamman temple, Singapore | |

| Devanagari | कृष्ण |

| Sanskrit transliteration | Kṛṣṇa |

| Affiliation | Svayam Bhagavan, Paramatman |

| Abode | Goloka Vrindavana, Gokula, Dwarka |

| Weapon |

Sudarshana Chakra Kaumodaki |

| Consort | Radha, Rukmini, Satyabhama, Jambavati, Kalindi, Mitravinda, Nagnajiti, Bhadra, Lakshmana and other 16,000 or 16,100 junior queens[1] |

| Parents | Devaki and Vasudeva, Yashoda (foster mother) and Nanda Baba (foster father) |

| Siblings | Balarama, Subhadra |

| Mount | Garuda |

| Texts | Mahabharata, Bhagavad Gita, Vishnu Purana, Bhagavata Purana |

| Festivals | Krishna Janmashtami, Holi |

| Part of a series on |

| Vaishnavism |

|---|

|

|

Sampradayas |

|

Philosophers–acharyas |

|

Related traditions |

|

|

Krishna (/ˈkrɪʃnə/; Sanskrit: कृष्ण, Kṛṣṇa in IAST, pronounced [ˈkr̩ʂɳə]) is a major Hindu deity worshiped in a variety of different perspectives. Krishna is recognised as the Svayam Bhagavan in his own right or as the complete/absolute incarnation of Lord Vishnu. Krishna is one of the most widely revered and popular of all Hindu deities.[2] Krishna's birthday is celebrated every year by Hindus on the eighth day (Ashtami) of the Krishna Paksha (dark fortnight) of the month of Shraavana in the Hindu calendar.[3]

Krishna is also known as Govinda, Mukunda, Madhusudhana, and Vasudeva. Krishna is often described and portrayed as an infant eating butter; a young boy playing a flute, as in the Bhagavata Purana;[4] a young man along with Radha; a young man surrounded by women; or as an elder giving direction and guidance, as in the Bhagavad Gita.[5] The stories of Krishna appear across a broad spectrum of Hindu philosophical and theological traditions.[6] They portray him in various perspectives: a god-child, a prankster, a model lover, a divine hero, and the Supreme Being.[7] The principal scriptures discussing Krishna's story are the Srimad Bhagavatam, the Mahabharata, the Harivamsa, the Bhagavata Purana, and the Vishnu Purana. The anecdotes and narratives of Krishna, in topic, are generally titled as Krishna Leela.

Worship of the deity Krishna, either in the form of deity Krishna or in the form of Vasudeva, Bala Krishna or Gopala can be traced to as early as the 4th Century BC.[8][9] Worship of Krishna as Svayam Bhagavan, or the Supreme Being known as Krishnaism, arose in the Middle Ages in the context of the Bhakti movement. From the 10th Century AD, Krishna became a favorite subject in performing arts and regional traditions of devotion developed for forms of Krishna, such as Jagannatha in Odisha, Vithoba in Maharashtra and Shrinathji in Rajasthan. Since the 1960s the worship of Krishna has also spread to the Western world and to Africa largely due to the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON).[10] Gaudia Math is also a leading proponent of Krishna worship.

Some religiously oriented scholars have tried to calculate dates for the birth of Krishna, some believing that Krishna, under the name of "Vasudeva Govinda Krishna Shauri," flourished as the ruler of Shuraseni and Vrishni tribes on the now-submerged island of Dwaraka (off the coast of Gujarat, India) sometime between 3200 and 3100 BC.[3]

Names and epithets

The name originates from the Sanskrit word Kṛṣṇa, which is primarily an adjective meaning "black," "dark" or "dark blue."[11] The waning moon is called Krishna Paksha, relating to the adjective meaning "darkening."[11] Sometimes it is also translated as "all-attractive," according to members of the Hare Krishna movement.[12]

As a name of Vishnu, Krishna is listed as the 57th name in the Vishnu Sahasranama. Based on his name, Krishna is often depicted in murtis as black or blue-skinned. Krishna is also known by various other names, epithets and titles, which reflect his many associations and attributes. Among the most common names are Mohnish "Attractive God," Mohan "enchanter," Govinda, "Finder of 'Go' - Veda or the cows" or Gopala, "Protector of the 'Go' - "Soul" or the cows" as 'Govinda' (like cowherds who protect cows, the Lord protect the souls of the living beings) which refer to Krishna's childhood in Braj (in present-day Uttar Pradesh).[13][14] Some of the distinct names may be regionally important—for instance, Jagannatha, a popular incarnation of Puri, Odisha in eastern India.[15]

Iconography

Krishna is easily recognized by his representations. Though his skin color may be depicted as black or dark in some representations, particularly in murtis, in other images such as modern pictorial representations, Krishna is usually shown with blue skin. He has been described as having skin the color of Jambul (Jamun, a purple-colored fruit). He is also known to have four symbols of the jambu fruit on his right foot as mentioned in the Srimad Bhagavatam commentary (verse 10.30.25), "Sri Rupa Cintamani" and "Ananda Candrika" by Srila Visvanatha Chakravarti Thakura.[16]

A steatite (soapstone) tablet unearthed from Mohenjo-daro, Larkana district, Sindh depicting a young boy uprooting two trees from which are emerging two human figures is an interesting archaeological find for fixing dates associated with Krishna. This image recalls the Yamalarjuna episode of Bhagavata and Harivamsa Purana. In this image, the young boy is Krishna, and the two human beings emerging from the trees are the two cursed gandharvas, identified as Nalakubara and Manigriva. Dr. E.J.H. Mackay, who did the excavation at Mohanjodaro, compares this image with the Yamalarjuna episode. Prof. V.S. Agrawal has also accepted this identification. Thus, it seems that the Indus valley people knew stories related to Krishna. This lone find may not establish Krishna as contemporary with Pre-Indus or Indus times, but, likewise, it cannot be ignored.[17]

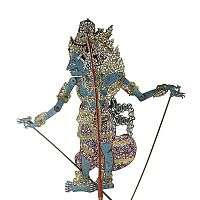

Krishna is often depicted wearing a silk golden yellow dhoti, and a peacock feather crown. Common depictions show him as a little boy, or as a young man in a characteristically relaxed pose, playing the flute.[18][19] In this form, he usually stands with one leg bent in front of the other in the Tribhanga posture, accompanied by cows, emphasising his position as the divine herdsman, Govinda, or with the gopis (milkmaids). Other depictions show him stealing butter from neighboring houses in the form of Gopkrishna; defeating the vicious serpent in the form of Navneet Chora or Gokulakrishna; or lifting the hill in the form of Giridhara Krishna. Still other depictions recount other childhood exploits.

The scene on the battlefield of the epic Mahabharata, notably where he addresses Pandava prince Arjuna in the Bhagavad Gita, is another common subject for representation. In these popular depictions, he is shown as the charioteer in the battle-field of Kurukshetra. In Vishvaroopa Darshana (Universal form) to Arjuna, Lord Krishna resumes the role of the often with supreme God's characteristics of Hindu religious art, such as multiple arms or heads, denoting power, and with attributes of Vishnu, such as the chakra or in his two-armed form as a charioteer. Cave paintings dated to 800 BCE in Mirzapur, Mirzapur district, Uttar Pradesh, show raiding horse-charioteers, one of whom is about to hurl a wheel, and who could potentially be identified as Krishna.[20]

Representations in temples often show him standing in a bent posture, holding a flute in his hand accompanied with his consort Radha and gopis.[21] Seldomly he is shown with his brother Balarama and sister Subhadra, or his queens Rukmini and Satyabhama

Krishna is also depicted and worshipped as a small child (Bala Krishna, Bāla Kṛṣṇa the child Krishna), crawling on his hands and knees, or dancing, often with butter or Laddu in his hand being Laddu Gopal.[22][23] Regional variations in the iconography of Krishna are seen in his different forms, such as Jaganatha of Odisha, Vithoba of Maharashtra,[24] Venkateswara (also Srinivasa or Balaji) in Andhra Pradesh, and Shrinathji in Rajasthan and also as a new born cosmic infant sucking his toe while floating on a banyan leef during the Pralaya (the cosmic dissolution) at the end of universe observed by sage Markandeya.[25]

Literary sources

The earliest text to explicitly provide detailed descriptions of Krishna as a personality is the epic Mahabharata which depicts Krishna as an incarnation of Vishnu.[26] Krishna is central to many of the main stories of the epic. The eighteen chapters of the sixth book (Bhishma Parva) of the epic that constitute the Bhagavad Gita contain the advice of Krishna to Arjuna, on the battlefield. Krishna is already an adult in the epic, although there are allusions to his earlier exploits. The Harivamsa, a later appendix to this epic, contains the earliest detailed version of Krishna's childhood and youth.

The Rig Veda 1.22.164 sukta 31 mentions a herdsman "who never stumbles".[27] Some Vaishnavite scholars, such as Bhaktivinoda Thakura, claim that this herdsman refers to Krishna.[28] Ramakrishna Gopal Bhandarkar also attempted to show that "the very same Krishna" made an appearance, e.g. as the drapsa ... krishna "black drop" of RV 8.96.13.[29] Some authors have also likened prehistoric depictions of deities to Krishna.

Chandogya Upanishad (3.17.6), dated between 8th and 6th century BCE, mentions Vasudeva Krishna as the son of Devaki and the disciple of Ghora Angirasa, the seer who preached his disciple the philosophy of ‘Chhandogya.’ Having been influenced by the philosophy of ‘Chhandogya’ Krishna in the Bhagavadgita while delivering the discourse to Arjuna on the battlefield of Kurukshetra discussed about sacrifice, which can be compared to purusha or the individual.[30][31][32][33]

Yāska's Nirukta, an etymological dictionary around 6th century BC, contains a reference to the Shyamantaka jewel in the possession of Akrura, a motif from well known Puranic story about Krishna.[34] Shatapatha Brahmana and Aitareya-Aranyaka, associate Krishna with his Vrishni origins.[35]

Pāṇini, the ancient grammarian and author of Asthadhyayi (probably belonged to 5th century or 6th century BC) mentions a character called Vāsudeva, son of Vasudeva, and also mentions Kaurava and Arjuna which testifies to Vasudeva Krishna, Arjuna and Kauravas being contemporaries.[30][36][37]

Megasthenes (350 – 290 BC) a Greek ethnographer and an ambassador of Seleucus I to the court of Chandragupta Maurya made reference to Herakles in his famous work Indica. Many scholars have suggested that the deity identified as Herakles was Krishna. According to Arrian, Diodorus, and Strabo, Megasthenes described an Indian tribe called Sourasenoi, who especially worshipped Herakles in their land, and this land had two cities, Methora and Kleisobora, and a navigable river, the Jobares. As was common in the ancient period, the Greeks sometimes described foreign gods in terms of their own divinities, and there is a little doubt that the Sourasenoi refers to the Shurasenas, a branch of the Yadu dynasty to which Krishna belonged; Herakles to Krishna, or Hari-Krishna: Methora to Mathura, where Krishna was born; Kleisobora to Krishnapura, meaning "the city of Krishna"; and the Jobares to the Yamuna, the famous river in the Krishna story. Quintus Curtius also mentions that when Alexander the Great confronted Porus, Porus's soldiers were carrying an image of Herakles in their vanguard.[38]

The name Krishna occurs in Buddhist writings in the form Kānha, phonetically equivalent to Krishna.[39]

The Ghata-Jâtaka (No. 454) gives an account of Krishna's childhood and subsequent exploits which in many points corresponds with the Brahmanic legends of his life and contains several familiar incidents and names, such as Vâsudeva, Baladeva, Kaṃsa. Yet it presents many peculiarities and is either an independent version or a misrepresentation of a popular story that had wandered far from its home.

Jain tradition also shows that these tales were popular and were worked up into different forms, for the Jains have an elaborate system of ancient patriarchs which includes Vâsudevas and Baladevas. Krishna is the ninth of the Black Vâsudevas and is connected with Dvâravatî or Dvârakâ. He will become the twelfth tîrthankara of the next world-period and a similar position will be attained by Devakî, Rohinî, Baladeva and Javakumâra, all members of his family. This is a striking proof of the popularity of the Krishna legend outside the Brahmanic religion.[40]

According to Arthasastra of Kautilya (4th century BCE) Vāsudeva was worshiped as supreme Deity in a strongly monotheistic format.[36]

Around 150 BC, Patanjali in his Mahabhashya quotes a verse: "May the might of Krishna accompanied by Samkarshana increase!" Other verses are mentioned. One verse speaks of "Janardhana with himself as fourth" (Krishna with three companions, the three possibly being Samkarshana, Pradyumna, and Aniruddha). Another verse mentions musical instruments being played at meetings in the temples of Rama (Balarama) and Kesava (Krishna). Patanjali also describes dramatic and mimetic performances (Krishna-Kamsopacharam) representing the killing of Kansa by Vasudeva.[41][42]

In the 1st century BC, there seems to be evidence for a worship of five Vrishni heroes (Balarama, Krishna, Pradyumna, Aniruddha and Samba) for an inscription has been found at Mora near Mathura, which apparently mentions a son of the great satrap Rajuvula, probably the satrap Sodasa, and an image of Vrishni, "probably Vasudeva, and of the "Five Warriors".[43] Brahmi inscription on the Mora stone slab, now in the Mathura Museum.[44][45]

Many Puranas tell Krishna's life-story or some highlights from it. Two Puranas, the Bhagavata Purana and the Vishnu Purana, that contain the most elaborate telling of Krishna's story and teachings are the most theologically venerated by the Vaishnava schools.[46] Roughly one quarter of the Bhagavata Purana is spent extolling his life and philosophy.

Life

This summary is a historical account, based on literary details from the Mahābhārata, the Harivamsa, the Bhagavata Purana and the Vishnu Purana. The scenes from the narrative are set in ancient India mostly in the present states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Haryana, Delhi and Gujarat.

Birth

Krishna was born to Devaki and her husband, Vasudeva on 27th July 3112 BCE on Earth in the Yadava clan; a prince named Kansa (who was actually an Asura by birth) had wreaked quite a havoc. During his sister Devaki's wedding ceremony, a divine prophecy (loud voice from the sky- Akasha Vani in Samskrutam) prophesied that the 8th son of Kansa's sister Devaki would kill Kansa.

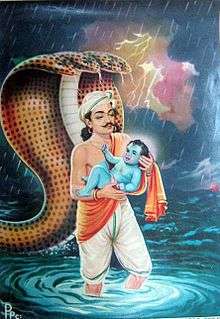

Out of affection for Devaki, Kansa did not kill her outright. He did, however, send his sister and her husband (Vasudeva) and his father King Ugrasen to prison. Lord Vishnu himself later appeared to Devaki and Vasudeva and told them that he himself would be their eighth son and kill Kansa and destroy sin in the world. In the story of Krishna, the deity is the agent of conception and also the offspring. Because of his sympathy for the earth, the almighty lord Vishnu himself descended into the womb of Devaki and was born as her son, Vaasudeva (i.e., Krishna).[47][48][49] The incarnation of Sri Krishna is a virgin conception. This is similar to the case of the virgin Kunti, the mother of the Pandavas referenced contemporaneously with the story of Krishna in the Mahabharata. She also has a divine conception and virgin birth of warrior-hero Karna and the Pandavas.[50] Devaki was married to Vasudeva and had already given birth to 7 children. Brahmarishi Narada created confusion as to which child would kill Kansa when he said "who knows what form the end might take". He also insinuated that the 8th son could be the first of 8 or the last of eight. He then said that the act of the God cannot be understood by humans and left the prophecy up to interpretation. Because Kansa was uncertain of which of his 8 nephews would kill him, he brutally murdered all six of the children that Devaki had already given birth to by bashing their heads in. When the 8th child was born, he was the reincarnation of Lord Vishnu, Lord Krishna. Vasudeva secretly carried the infant Krishna out of the prison and exchanged children with Nanda, a kinsman of Vasudeva, for his daughter. This daughter was yog maya, an incarnation of (Durga). She warned Kansa that his death had arrived in his kingdom and then disappeared. Krishna was adopted by Nanda and his wife Yasoda[51][52][53][54] in Gokula (in present-day Mathura district). Two of his other siblings also survived, Balarama (Devaki's seventh child, miraculously transferred to the womb of Rohini, Vasudeva's first wife) and Subhadra (daughter of Vasudeva and Rohini, born much later than Balarama and Krishna).[55]

Krishna belonged to the Vrishni clan of Yadavas from Mathura,[56] and was the eighth son born to the princess Devaki, and her husband Vasudeva.

Mathura (in present-day Mathura district, Uttar Pradesh) was the capital of the Yadavas, to which Krishna's parents Vasudeva and Devaki belonged. King Kansa, Devaki's brother,[57] had ascended the throne by imprisoning his father, King Ugrasena.

Childhood and youth

Nanda was the head of a community of cow-herders in Gokul. Due to the countinous threat by the demons sent by Kansa, Lord Krishna suggested to his father and the villagers that they leave Gokul and go to Vrindavan. Later, with the help of Vrishabanu (who was both Radha's father and Nand's friend) helped Nand and his villagers to settle in Vridavan. Finally, they settled in Vrindavana. Although, the rampage of demons continued in Vrindavan, in the lord's presence they were reduced to dust. The stories of Krishna's childhood and youth tell how he became a cow herder,[58] his mischievous pranks as Makhan Chor (butter thief), his foiling of attempts to take his life, and his role as a protector who stole the hearts of the people in both Gokul and Vrindavana.

Krishna killed the demoness Putana, disguised as a wet nurse, Shaktasur, and the tornado demon Trinavarta both sent by Kansa to kill Krishna in Gokul. The other miracles like changing a basket of fruit into precious stones and jewels of a fruit vendor due to her offering of fruit to the Lord for her love for the godchild is well known. He later in Vrindavan, tamed the serpent Kāliyā, who had poisoned the waters of Yamuna river, thus leading to the death of the cowherds. In Hindu art, Krishna is often depicted dancing on the multi-hooded Kāliyā. He also defeated demons like Dhenukasura, Vatsasura, Keshi, Aghasura, Arishtasura, Bakasura, Vyomasura, Pralambasura and many others in Vrindavan.

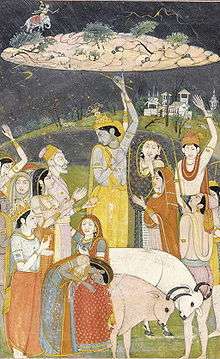

Krishna lifted the Govardhana hill and taught Indra, the king of the devas, a lesson to protect the native people of Vrindavana from persecution by Indra and prevent the devastation of the pasture land of Govardhan. Indra had too much pride and was angry when Krishna advised the people of Vrindavana to take care of their animals and their environment that provide them with all their necessities, instead of worshipping Indra annually by spending their resources.[59][60] In the view of some, the spiritual movement started by Krishna had something in it which went against the orthodox forms of worship of the Vedas.[61] In Bhagavat Purana, Krishna says that the rain came from the nearby hill Govardhana, and advised that the people worship the hill instead of Indra. This made Indra furious, so he punished them by sending out a great storm and rain which lasted for seven days and seven nights. Krishna then lifted Govardhan and held it over the people like an umbrella. This reduced Indra's pride and he felt guilt of his act and sought forgivness from the lord in the form of a sage.

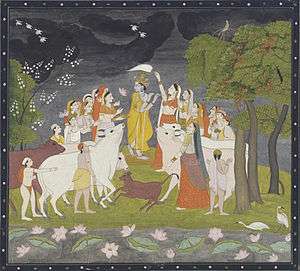

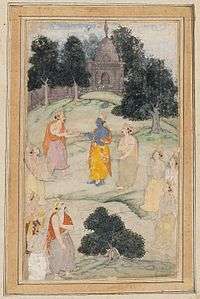

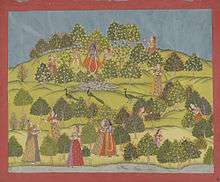

The stories of his play with the gopis (milkmaids) of Vrindavana, especially Radha (daughter of Vrishbhanu, one of the original residents of Vrindavan) became known as the Rasa lila and were romanticised in the poetry of Jayadeva, author of the Gita Govinda. These became important as part of the development of the Krishna bhakti traditions worshiping Radha Krishna.[62]

Krishna's childhood reinforces the Hindu concept of lila, playing for fun and enjoyment and not for sport or gain. His interaction with the gopis at the rasa dance or Rasa-lila is a great example of this. Krishna played his flute and the gopis came immediately from whatever they were doing, to the banks of the Yamuna River, and joined him in singing and dancing. Even those who could not physically be there joined him through meditation.[63] The story of Krishna's battle with Kāliyā also supports this idea in the sense of him dancing on Kāliyā's many hoods. Even though he is doing battle with the serpent, he is in no real danger and treats it like a game. He is a protector, but he only appears to be a young boy having fun. With his supreme powers, Krishna killed innumerable powerful demons (who had been born as demons because of curses or fate) so he could help them to attain salvation.[64] This idea of having a playful god is very important in Hinduism. The playfulness of Krishna has inspired many celebrations like the Rasa-lila and the Janmashtami : where they make human pyramids to break open handis (clay pots) hung high in the air that spill buttermilk all over the group after being broken by the person at the top. This is meant to be a fun celebration and it gives the participants a sense of unity. Many believe that lila being connected with Krishna gives Hindus a deeper connection to him and thus a deeper connection to Vishnu also; seeing as Krishna is an incarnation of Vishnu. Theologists, like Kristin Johnston Largen, believe that Krishna's childhood can even inspire other religions to look for lila in deities so that they have a chance to experience a part of their faith that they may not have previously seen.[65]

The prince

On his return to Mathura as a young man, Krishna overthrew and killed his maternal uncle, Kansa, after quelling several assassination attempts from Kansa's followers. He reinstated Kansa's father, Ugrasena, as the king of the Yadavas and became a leading prince at the court.[67] During this period, he became a friend of Arjuna and the other Pandava princes of the Kuru kingdom, who were his cousins. Later, he took his Yadava subjects to the city of Dwaraka (in modern Gujarat) and established a new kingdom there. Krishna was the prince and commander of the Armies of Dwaraka, while Balarama was crown prince and de facto administrator as King Ugrasena was still the emperor of Dwaraka but reigned over Mathura.[68] According to the legends, the marriage of Sri Krishna is for the sake of the souls who sincerely devoted to the lord sought his help to attain moksha (Salvation). Accepting their prayers the lord himself agreed to be their protector. Thus, the marriage of the lord is not to do anything for physical union, but, it is only for the union of soul of the living (jeevaathma) with the superior creator (parmaathma)

Krishna married Rukmini, the Vidarbha princess, by abducting her, at her request, from her proposed wedding with Shishupala. He married eight queens—collectively called the Ashtabharya—including Rukmini, Satyabhama, Jambavati, Kalindi, Mitravinda, Nagnajiti, Bhadra and Lakshmana.[69][70] Krishna subsequently married 16,000 or 16,100 maidens who were held captive by the demon Narakasura, to save their honour.[71][72] Krishna killed the demon and released them all. According to social custom of the time, all of the captive women were degraded, and would be unable to marry, as they had been under the Narakasura's control. However Krishna married them to reinstate their status in the society. This symbolic wedding with 16,100 abandoned daughters was more of a mass rehabilitation.[73] In Vaishnava traditions, Krishna's wives are forms of the goddess Lakshmi — consort of Vishnu, or special souls who attained this qualification after many lifetimes of austerity, while his two queens, Rukmani and Satyabhama, are expansions of Lakshmi.[74]

When Yudhishthira was assuming the title of emperor, he had invited all the great kings to the ceremony and while paying his respects to them, he started with Krishna because he considered Krishna to be the greatest of them all. While it was a unanimous feeling amongst most present at the ceremony that Krishna should get the first honours, his cousin Shishupala felt otherwise and started berating Krishna. Due to a vow given to Shishupal's mother, Krishna forgave a hundred verbal abuses by Shishupal, and upon the one hundred and first, he assumed his Virat (universal) form and killed Shishupal with his Chakra. The blind king Dhritarashtra also obtained divine vision to be able to see this form of Krishna during the time when Duryodana tried to capture Krishna when he came as a peace bearer before the great Mahabharat War. Essentially, Shishupala and Dantavakra were both re-incarnations of Vishnu's gate-keepers Jaya and Vijaya, who were cursed to be born on Earth, to be delivered by the Vishnu back to Vaikuntha.[75]

Kurukshetra War and Bhagavad Gita

Lord Krishna was a mighty Maha Maharathi, greater than any past, present or future warrior. He possessed all three ultimate weapons of the Trimurthi, the Brahma Danda, the Pashupatastra and the Vaishnavastra. He also possessed the Narayanastra, NagaPasha and the Vasavi Shakti and all other divine astras. He was one of the very few people who knew the secret of both entering into and coming out of Chakra Vyuha. Lord krishna is considered as the greatest warrior in all of Hindu mythology. He never lost any battle that he fought and was uniformly successful in all his wars. He was the first to defeat mighty Jarasandha, the ruler of Magadha even though he couldn't kill him. Once battle seemed inevitable, Krishna offered both sides the opportunity to choose between having either his army called Narayani Sena or himself alone, but on the condition that he personally would not raise any weapon. Arjuna, on behalf of the Pandavas, chose to have Krishna on their side, and Duryodhana, Kaurava prince, chose Krishna's army. At the time of the great battle, Krishna acted as Arjuna's charioteer, since this position did not require the wielding of weapons.

Upon arrival at the battlefield, and seeing that the enemies are his family, his grandfather, his cousins and loved ones, Arjuna is moved and says his heart does not allow him to fight and he would rather prefer to renounce the kingdom and put down his Gandiv (Arjuna's bow). Krishna then advises him about the battle, with the conversation soon extending into a discourse which was later compiled as the Bhagavad Gita.[76]

Krishna asked Arjuna, "Have you within no time, forgotten the Kauravas' evil deeds such as not accepting the eldest brother Yudhishtira as King, usurping the entire Kingdom without yielding any portion to the Pandavas, meting out insults and difficulties to Pandavas, attempt to murder the Pandavas in the Barnava lac guest house, publicly attempting to disrobe and disgracing Draupadi. Krishna further exhorted in his famous Bhagavad Gita, "Arjuna, do not engage in philosophical analyses at this point of time like a Pundit. You are aware that Duryodhana particularly have long harboured jealousy and hatred for you Pandavas and badly want to prove their hegemony. You are aware that Bhishmacharya and your Teachers are tied down to their dharma of protecting the unitarian power of the Kuru throne. Moreover, you Arjuna, are only a mortal appointee to carry out my divine will, since the Kauravas are destined to die either way, due to their heap of sins. Open your eyes O Bhaarata and know that I encompass the Karta, Karma and Kriya, all in myself. There is no scope for contemplation now or remorse later, it is indeed time for war and the world will remember your might and immense powers for time to come. So rise O Arjuna!, tighten up your Gandiva and let all directions shiver till their farthest horizons, by the reverberation of its string."

.jpg)

Krishna had a profound effect on the Mahabharata war and its consequences. He had considered the Kurukshetra war to be a last resort after voluntarily acting as a messenger in order to establish peace between the Pandavas and Kauravas. But, once these peace negotiations failed and was embarked into the war, then he became a clever strategist. During the war, upon becoming angry with Arjuna for not fighting in true spirit against his ancestors, Krishna once picked up a carriage wheel in order to use it as a weapon to challenge Bhishma. Upon seeing this, Bhishma dropped his weapons and asked Krishna to kill him. However, Arjuna apologised to Krishna, promising that he would fight with full dedication hereafter, and the battle continued. Krishna had directed Yudhishthira and Arjuna to return to Bhishma the boon of "victory" which he had given to Yudhishthira before the war commenced, since he himself was standing in their way to victory. Bhishma understood the message and told them the means through which he would drop his weapons—which was if a woman entered the battlefield. Next day, upon Krishna's directions, Shikhandi (Amba reborn) accompanied Arjuna to the battlefield and thus, Bhishma laid down his arms. This was a decisive moment in the war because Bhishma was the chief commander of the Kaurava army and the most formidable warrior on the battlefield. Krishna aided Arjuna in killing Jayadratha, who had held the other four Pandava brothers at bay while Arjuna's son Abhimanyu entered Drona's Chakravyuha formation—an effort in which he was killed by the simultaneous attack of eight Kaurava warriors. Krishna also caused the downfall of Drona, when he signalled Bhima to kill an elephant called Ashwatthama, the namesake of Drona's son. Pandavas started shouting that Ashwatthama was dead but Drona refused to believe them saying he would believe it only if he heard it from Yudhishthira. Krishna knew that Yudhishthira would never tell a lie, so he devised a clever ploy so that Yudhishthira wouldn't lie and at the same time Drona would be convinced of his son's death. On asked by Drona, Yudhishthira proclaimed

Ashwathama Hatahath, naro va Kunjaro va

i.e. Ashwathama had died but he was nor sure whether it was a Drona's son or an elephant. But as soon as Yudhishthira had uttered the first line, Pandava army on Krishna's direction broke into celebration with drums and conchs, in the din of which Drona could not hear the second part of the Yudhishthira's declaration and assumed that his son indeed was dead. Overcome with grief he laid down his arms, and on Krishna's instruction Dhrishtadyumna beheaded Drona.

When Arjuna was fighting Karna, the latter's chariot's wheels sank into the ground. While Karna was trying to take out the chariot from the grip of the Earth, unarmed, Krishna reminded Arjuna how Karna and the other Kauravas had broken all rules of battle while simultaneously attacking and killing Abhimanyu, and he convinced Arjuna to do the same in revenge in order to kill Karna. Thus Arjuna broke all the rules of the battle too. During the final stage of the war, when Duryodhana was going to meet his mother Gandhari for taking her blessings which would convert all parts of his body on which her sight falls to diamond, Krishna tricks him to wearing banana leaves to hide his groin. When Duryodhana meets Gandhari, her vision and blessings fall on his entire body except his groin and thighs, and she becomes unhappy about it because she was not able to convert his entire body to diamond. When Duryodhana was in a mace-fight with Bhima, Bhima's blows had no effect on Duryodhana. Upon this, Krishna reminded Bhima of his vow to kill Duryodhana by hitting him on the thigh, and Bhima did the same to win the war despite it being against the rules of mace-fight (since Duryodhana had himself broken Dharma in all his past acts). Thus, Krishna's unparalleled strategy helped the Pandavas win the Mahabharata war by bringing the downfall of all the chief Kaurava warriors, without lifting any weapon. He also brought back to life Arjuna's grandson Parikshit, who had been attacked by a Brahmastra weapon from Ashwatthama while he was in his mother's womb. Parikshit became the Pandavas' successor.

Family

Krishna had eight principal wives, also known as Ashtabharya: Rukmini, Satyabhama, Jambavati, Nagnajiti, Kalindi, Mitravinda, Bhadra and Lakshmana. Besides them Krishna married 16,100 more women (number varies in scriptures), whom he had rescued from Narakasura's palace after killing Narakasura. He married them all to save them from destruction and notoriety. He gave them shelter in his new palace and a respectful place in society.

The Bhagavata Purana, Vishnu Purana, and Harivamsa list the children of Krishna from the Ashtabharya with some variation, while Rohini's sons are interpreted to represent the unnumbered children of his junior wives. Most well-known among his sons are Pradyumna, the eldest son of Krishna (and Rukmini). Pradyumna is one in 24 Keshava Namas (names), praised in all pujas.[78] and Samba, the son of Jambavati, whose actions led to the destruction of Krishna's clan.

Later life

According to Mahabharata, the Kurukshetra war resulted in the death of all the hundred sons of Gandhari. On the night before Duryodhana's death, Krishna visited Gandhari to offer his condolences. Gandhari felt that Krishna knowingly did not put an end to the war, and in a fit of rage and sorrow, Gandhari cursed that Krishna, along with everyone else from the Yadu dynasty, would perish after 36 years. Krishna himself knew and wanted this to happen as he felt that the Yadavas had become very haughty and arrogant (adharmi), so he ended Gandhari's speech by saying "tathastu" (so be it). According to Srimad Bhagavatham, Rishi Vyas cursed yadavas (due to a tactful play by Yadavas with Rishi Vyas) saying, your entire community will die.

Thirty-six years later, a fight broke out between the Yadavas at a festival, who killed each other. Krishna's elder brother, Balarama, then gave up his body using Yoga. Krishna retired into the forest and started meditating under a tree. The Mahabharata also narrates the story of a hunter who becomes an instrument for Krishna's departure from the world. The hunter Jara, mistook Krishna's partly visible left foot for that of a deer, and shot an arrow, wounding him mortally. Krishna told Jara, "O Jara, you were Bali in your previous birth, killed by myself as Rama in Tretayuga. Here you had a chance to even it and since all acts in this world are done as desired by me, you need not worry for this". Then Krishna, with four handed form ascended to his abode.[79][80][81][82] The news was conveyed to Hastinapur and Dwaraka by eyewitnesses to this event.[83] The place of this incident is believed to be Bhalka, near Somnath temple.[84][85]

According to Puranic sources,[86] Krishna's departure marks the end of Dvapara Yuga and the start of Kali Yuga, which is dated to 17/18 February 3102 BCE.[87] Vaishnava teachers such as Ramanujacharya and Gaudiya Vaishnavas held the view that the body of Krishna is completely spiritual and never decays (Achyuta) as this appears to be the perspective of the Bhagavata Purana. Lord Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (an incarnation of Lord Sri Krishna according to the Bhavishya Purana) exhorted, "Krishna Naama Sankirtan" i.e. the constant chanting of the Krishna's name is the supreme healer in Kali Yuga. It destroys sins and purifies the hearts through Bhakti and ensures universal peace.

Krishna never appears to grow old or age at all in the historical depictions of the Puranas despite passing of several decades, but there are grounds for a debate whether this indicates that he has no material body, since battles and other descriptions of the Mahabhārata epic show clear indications that he seems to be subject to the limitations of nature.[88] While battles apparently seem to indicate limitations, Mahabharata also shows in many places where Krishna is not subject to any limitations through episodes Duryodhana trying to arrest Krishna where his body burst into fire showing all creation within him.[89] Krishna is also explicitly described as without deterioration elsewhere.[90]

Proposed datings

Some religiously oriented scholars have tried to assign dates to Krishna himself and to the Kurukshetra war:

- According to drikpanchang.com, the date of Krishna's birth, known as Janmashtami,[91] is 21 February 3228 BCE.[92]

- Dr. P. V. Holay suggests 13 November 3143 BCE as the beginning of the Kurukshetra war.[93]

- Dr. Narhari Achar[94] states that Krishna lived sometime between 3200 BC and 3112 BCE. Achar's findings were based on the interpretation of the constellations, star positions and thithis mentioned in the Mahabharata. He also stated that the Kurukshetra war took place in 3139 BCE.[95]

- A. K. Bansal calculated 21 July 3228 BCE as the birth date of Sri Krishna.[96][97]

- B. V. Raman states that Sri Krishna was born on 19 July 3228 BCE.

- Dr. Manish Pandit's 2009 study places Krishna's life in the 31st century BC

- Dr. P.V. Vartak places Lord Krishna's birth year as 5561 BCE.

- Jain tradition consider Krishna to be cousin of Neminatha,[98] who is believed to be born 84000 years before Parshvanatha[99] (i.e. 85th millennium BC).[100]

A paper presented in a conference in 2004 by a group of archaeologists, religious scholars and astronomers from Somnath Trust of Gujarat, which was organised at Prabhas Patan, the supposed location of the death of Sri Krishna, fixes the death of Sri Krishna on 18 February 3102 BC at the age of 125 years and 7 months.[101] The death date was deduced from Puranic hints such as the Matsya Purana mention which says Krishna was 89 years old when the Kurukshetran War was fought and the verses from Mahabharata which states that Sri Krishna lived 36 years after the Kurukshetra war. Despite skepticism from some parts of the scientific fraternity these findings found immense popular support in India.[3]

Worship

Vaishnavism

The worship of Krishna is part of Vaishnavism, which regards Vishnu as the supreme God and venerates his associated avatars, their consorts, and related saints and teachers. Krishna is especially looked upon as a full manifestation of Vishnu, and as one with Vishnu himself.[102] However the exact relationship between Krishna and Vishnu is complex and diverse,[103] where Krishna is sometimes considered an independent deity, supreme in his own right.[104] Out of many deities, Krishna is particularly important, and traditions of Vaishnava lines are generally centred either on Vishnu or on Krishna as supreme. The term Krishnaism has been used to describe the sects of Krishna, reserving the term "Vaishnavism" for sects focusing on Vishnu in which Krishna is an avatar, rather than as a transcendent Supreme Being.[105]

All Vaishnava traditions recognise Krishna as eighth avatar of Vishnu; others identify Krishna with Vishnu; while traditions, such as Gaudiya Vaishnavism,[106][107] Vallabha Sampradaya and the Nimbarka Sampradaya, regard Krishna as the Svayam Bhagavan, original form of God.[108][109][110][111][112] Swaminarayan, the founder of the Swaminarayan Sampraday, also worshipped Krishna as God himself. "Greater Krishnaism" corresponds to the second and dominant phase of Vaishnavism, revolving around the cults of the Vasudeva, Krishna, and Gopala of the late Vedic period.[113] Today the faith has a significant following outside of India as well.[114]

Early traditions

The deity Krishna-Vasudeva (kṛṣṇa vāsudeva "Krishna, the son of Vasudeva") is historically one of the earliest forms of worship in Krishnaism and Vaishnavism.[8][34] It is believed to be a significant tradition of the early history of the worship of Krishna in antiquity.[9][115] This tradition is considered as earliest to other traditions that led to amalgamation at a later stage of the historical development. Other traditions are Bhagavatism and the cult of Gopala, that along with the cult of Bala Krishna form the basis of current tradition of monotheistic religion of Krishna.[116][117] Some early scholars would equate it with Bhagavatism,[9] and the founder of this religious tradition is believed to be Krishna, who is the son of Vasudeva, thus his name is Vāsudeva; he is said to be historically part of the Satvata tribe, and according to them his followers called themselves Bhagavatas and this religion had formed by the 2nd century BC (the time of Patanjali), or as early as the 4th century BC according to evidence in Megasthenes and in the Arthasastra of Kautilya, when Vāsudeva was worshiped as supreme deity in a strongly monotheistic format, where the supreme being was perfect, eternal and full of grace.[9] In many sources outside of the cult, the devotee or bhakta is defined as Vāsudevaka.[118] The Harivamsa describes intricate relationships between Krishna Vasudeva, Sankarsana, Pradyumna and Aniruddha that would later form a Vaishnava concept of primary quadrupled expansion, or avatar."[119]

Bhakti tradition

Bhakti, meaning devotion, is not confined to any one deity. However Krishna is an important and popular focus of the devotional and ecstatic aspects of Hindu religion, particularly among the Vaishnava sects.[106][120] Devotees of Krishna subscribe to the concept of lila, meaning 'divine play', as the central principle of the Universe. The lilas of Krishna, with their expressions of personal love that transcend the boundaries of formal reverence, serve as a counterpoint to the actions of another avatar of Vishnu: Rama, "He of the straight and narrow path of maryada, or rules and regulations."[107]

The bhakti movements devoted to Krishna became prominent in southern India in the 7th to 9th centuries AD. The earliest works included those of the Alvar saints of the Tamil country.[121] A major collection of their works is the Divya Prabandham. The Alvar Andal's popular collection of songs Tiruppavai, in which she conceives of herself as a gopi, is the most famous of the oldest works in this genre.[122][123] [124] Kulasekaraazhvaar's Mukundamala was another notable work of this early stage.

Spread of the Krishna-bhakti movement

The movement, which started in the 6th-7th century A.D. in the Tamil-speaking region of South India, with twelve Alvar (one immersed in God) saint-poets, who wrote devotional songs. The religion of Alvar poets, which included a woman poet, Andal, was devotion to God through love (bhakti), and in the ecstasy of such devotions they sang hundreds of songs which embodied both depth of feeling and felicity of expressions. The movement originated in South India during the seventh-century CE, spreading northwards from Tamil Nadu through Karnataka and Maharashtra; by the fifteenth century, it was established in Bengal and northern India[125]

While the learned sections of the society well versed in Sanskrit could enjoy works like Gita Govinda or Bilvamangala's Krishna-Karnamritam, the masses sang the songs of the devotee-poets, who composed in the regional languages of India. These songs expressing intense personal devotion were written by devotees from all walks of life. The songs of Meera and Surdas became epitomes of Krishna-devotion in north India.

These devotee-poets, like the Alvars before them, were aligned to specific theological schools only loosely, if at all. But by the 11th century AD, Vaishnava Bhakti schools with elaborate theological frameworks around the worship of Krishna were established in north India. Nimbarka (11th century AD), Vallabhacharya (15th century AD) and (Lord Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu an incarnation of Lord Sri Krishna according to the Bhavishya Purana) (16th century AD) all inspired by the teachings of Madhvacharya (11th century AD) were the founders of the most influential schools. These schools, namely Nimbarka Sampradaya, Vallabha Sampradaya and Gaudiya Vaishnavism respectively, see Krishna as the supreme God.

In the Deccan, particularly in Maharashtra, saint poets of the Varkari sect such as Dnyaneshwar, Namdev, Janabai, Eknath and Tukaram promoted the worship of Vithoba,[24] a local form of Krishna, from the beginning of the 13th century until the late 18th century.[7] In southern India, Purandara Dasa and Kanakadasa of Karnataka composed songs devoted to the Krishna image of Udupi. Rupa Goswami of Gaudiya Vaishnavism, has compiled a comprehensive summary of bhakti named Bhakti-rasamrita-sindhu.[120]

In the West

In 16th Century AD when Chaitanya Mahaprabhu launched the sankirtan movement of the congregational chanting of the holy names of the Lord (Krishna), he commissioned his closest associates to spread the movement everywhere. On the order of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, Nityananda Prabhu traveled extensively throughout Bengal, humbly begging everyone he met to chant the holy names and worship Radha-Krishna. Many Bengalis surrendered at his lotus feet, becoming his disciples and adopting the Gaudiya Vaisnava way of life. Among these disciples was Krishnananda Dutta Chaudhury,

In 1965, the Krishna-bhakti movement had spread outside India when its founder, Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, (who was instructed by his guru, Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura) traveled from his homeland in West Bengal to New York City. A year later in 1966, after gaining many followers, he was able to form the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), popularly known as the Hare Krishna movement. The purpose of this movement was to write about Krishna in English and to share the Gaudiya Vaishnava philosophy with people in the Western world by spreading the teachings of the saint Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. In an effort to gain attention, followers chanted the names of God in public locations. This chanting was known as hari-nama sankirtana and helped spread the teaching. Additionally, the practice of distributing prasad or "sanctified food" worked as a catalyst in the dissemination of his works. In the Hare Krishna movement, Prasad was a vegetarian dish that would be first offered to Krishna. The food's proximity to Krishna added a "spiritual effect," and was seen to "counteract material contamination affecting the soul." Sharing this sanctified food with the public, in turn, enabled the movement to gain new recruits and further spread these teachings.[10][126][127]

In South India

In South India, Vaishnavas usually belong to the Sri Sampradaya. The acharyas of the Sri Sampradaya have written reverentially about Krishna in most of their works like the Thiruppavai by Andal[128] and Gopala Vimshati by Vedanta Desika.[129] In South India, devotion to Krishna, as an avatar of Vishnu, spread in the face of opposition to Buddhism, Shaktism, and Shaivism and ritualistic Vedic sacrifices. The acharyas of the Sri Sampradaya like Manavala Mamunigal, Vedanta Desika strongly advocated surrender to Vishnu as the aim of the Vedas. Out of 108 Divya Desams there are 97 Divya Desams in South India.

Due to strong Vaishnava influence in Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Kerala, these states have many major Krishna temples and Janmashtami is one of the widely celebrated festivals in South India.

In the performing arts

While discussing the origin of Indian theatre, Horwitz talks about the mention of the Krishna story in Patanjali's Mahabhashya (c. 150 BC), where the episodes of slaying of Kansa (Kansa Vadha) and "Binding of the heaven storming titan" (Bali Bandha) are described.[130] Bhasa's Balacharitam and Dutavakyam (c. 400 BC) are the only Sanskrit plays centred on Krishna written by a major classical dramatist. The former dwells only on his childhood exploits and the latter is a one-act play based on a single episode from the Mahābhārata when Krishna tries to make peace between the warring cousins.[131]

The classical Indian dances, especially Odissi and Manipuri, draw heavily on the story. The 'Rasa lila' dances performed in Vrindavan shares elements with Kathak, and the Krisnattam, with some cycles, such as Krishnattam, traditionally restricted to the Guruvayur temple, the precursor of Kathakali.[132]

In other religions

Jainism

The Jain tradition lists of sixty-three Śalākāpuruṣa or notable figures include, amongst others, the twenty-four Tirthankaras and nine sets of this triad. One of these triads is Krishna as the Vasudeva, Balarama as the Baladeva and Jarasandha as the Prati-Vasudeva. He was a cousin of the twenty-second Tirthankara, Neminatha. The stories of these triads can be found in the Harivamsa Purana (8th century CE) of Jinasena (not be confused with its namesake, the addendum to Mahābhārata) and the Trishashti-shalakapurusha-charita of Hemachandra.[133][134]

In each age of the Jain cyclic time is born a Vasudeva with an elder brother termed the Baladeva. The villain is the Prati-vasudeva. Baladeva is the upholder of the Jain principle of non-violence. However, Vasudeva has to forsake this principle to kill the Prati-Vasudeva and save the world.[135][136]

Buddhism

The story of Krishna occurs in the Jataka tales in Buddhism,[137] in the Vaibhav Jataka as a prince and legendary conqueror and king of India.[138] In the Buddhist version, Krishna is called Vasudeva, Kanha and Keshava, and Balarama is his older brother, Baladeva. These details resemble that of the story given in the Bhagavata Purana. Vasudeva, along with his nine other brothers (each son a powerful wrestler) and one elder sister (Anjana) capture all of Jambudvipa (many consider this to be India) after beheading their evil uncle, King Kansa, and later all other kings of Jambudvipa with his Sudarshana Chakra. Much of the story involving the defeat of Kansa follows the story given in the Bhagavata Purana.[139]

As depicted in the Mahābhārata, all of the sons are eventually killed due to a curse of sage Kanhadipayana (Veda Vyasa, also known as Krishna Dwaipayana). Krishna himself is eventually speared by a hunter in the foot by mistake, leaving the sole survivor of their family being their sister, Anjanadevi of whom no further mention is made.[140]

Since Jataka tales are given from the perspective of Buddha's previous lives (as well as the previous lives of many of Buddha's followers), Krishna appears as the "Dhammasenapati" or "Chief General of the Dharma" and is usually shown being Buddha's "right-hand man" in Buddhist art and iconography.[141] The Bodhisattva, is born in this tale as one of his youngest brothers named Ghatapandita, and saves Krishna from the grief of losing his son.[138] The 'divine boy' Krishna as an embodiment of wisdom and endearing prankster forms a part of the pantheon of gods in Japanese Buddhism .[142]

Bahá'í Faith

Bahá'ís believe that Krishna was a "Manifestation of God", or one in a line of prophets who have revealed the Word of God progressively for a gradually maturing humanity. In this way, Krishna shares an exalted station with Abraham, Moses, Zoroaster, Buddha, Muhammad, Jesus, the Báb, and the founder of the Bahá'í Faith, Bahá'u'lláh.[143][144]

Ahmadiyya Islam

Members of the Ahmadiyya Community believe Krishna to be a great prophet of God as described by their founder, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad.

Ghulam Ahmad also claimed to be the likeness of Krishna as a latter day reviver of religion and morality whose mission was to reconcile man with God.[145] Ahmadis maintain that the Sanskrit term Avatar is synonymous with the term 'prophet' of the Middle Eastern religious tradition as God's intervention with man; as God appoints a man as his vicegerent upon earth. In Lecture Sialkot, Ghulam Ahmed wrote:

Let it be clear that Raja Krishna, according to what has been revealed to me, was such a truly great man that it is hard to find his like among the Rishis and Avatars of the Hindus. He was an Avatar—i.e., Prophet—of his time upon whom the Holy Spirit would descend from God. He was from God, victorious and prosperous. He cleansed the land of the Aryas from sin and was in fact the Prophet of his age whose teaching was later corrupted in numerous ways. He was full of love for God, a friend of virtue and an enemy of evil.[145]

Krishna is also called Murli Dhar. The flute of Krishna means the flute of revelation and not the physical flute. According to Ahmadis, Krishna lived like humans and was a prophet.[146][147]

Other

Krishna worship or reverence has been adopted by several new religious movements since the 19th century and he is sometimes a member of an eclectic pantheon in occult texts, along with Greek, Buddhist, biblical and even historical figures.[148] For instance, Édouard Schuré, an influential figure in perennial philosophy and occult movements, considered Krishna a Great Initiate; while Theosophists regard Krishna as an incarnation of Maitreya (one of the Masters of the Ancient Wisdom), the most important spiritual teacher for humanity along with Buddha.[149][150]

Krishna was canonised by Aleister Crowley and is recognised as a saint in the Gnostic Mass of Ordo Templi Orientis.[151][152]

See also

References

- ↑ John Stratton Hawley, Donna Marie Wulff (1982). The Divine Consort: Rādhā and the Goddesses of India. Motilal Banarsidass Publishe. ISBN 9780895811028.

- ↑ "Krishna". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- 1 2 3 "Krishna lived 125 years". Times of India.

- ↑ Knott 2000, p. 56

- ↑ Knott 2000, p. 36, p. 15

- ↑ Richard Thompson, Ph.D. (December 1994). "Reflections on the Relation Between Religion and Modern Rationalism". Retrieved 2008-04-12.

- 1 2 Mahony, W.K. (1987). "Perspectives on Krsna's Various Personalities". History of Religions. American Oriental Society. 26 (3): 333–335. doi:10.1086/463085. JSTOR 1062381.

- 1 2 Hein, Norvin. "A Revolution in Kṛṣṇaism: The Cult of Gopāla". History of Religions. 25: 296–317. doi:10.1086/463051. JSTOR 1062622.

- 1 2 3 4 Hastings, James Rodney (2003) [1908–26]. Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics. 4. John A Selbie (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: Kessinger Publishing, LLC. p. 476. ISBN 0-7661-3673-6. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

The encyclopedia will contain articles on all the religions of the world and on all the great systems of ethics. It will aim at containing articles on every religious belief or custom, and on every ethical movement, every philosophical idea, every moral practice.

pp.540-42 - 1 2 Selengut, Charles (1996). "Charisma and Religious Innovation:Prabhupada and the Founding of ISKCON". ISKCON Communications Journal. 4 (2). Archived from the original on 13 July 2011.

- 1 2

- ↑ Rosen, Steven (2006). Essential Hinduism. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-275-99006-0.

- ↑ Bryant 2007, p. 17

- ↑ Hiltebeitel, Alf (2001). Rethinking the Mahābhārata: a reader's guide to the education of the dharma king. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 251–53, 256, 259. ISBN 0-226-34054-6.

- ↑ B.M.Misra. Orissa: Shri Krishna Jagannatha: the Mushali parva from Sarala's Mahabharata. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 0-19-514891-6. in Bryant 2007, p. 139

- ↑ Vishvanatha, Cakravarti Thakura (2011). Sarartha-darsini (Bhanu Swami ed.). Sri Vaikunta Enterprises. p. 790. ISBN 978-81-89564-13-1.

- ↑ Mackay's report part 1, pp.344–45, Part 2, plate no.90, object no. D.K.10237

- ↑ The Encyclopedia Americana. [s.l.]: Grolier. 1988. p. 589. ISBN 0-7172-0119-8.

- ↑ Benton, William (1974). The New Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 885. ISBN 9780852292907.

- ↑ D. D. Kosambi (1962), Myth and Reality: Studies in the Formation of Indian Culture, New Delhi, CHAPTER I: SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC ASPECTS OF THE BHAGAVAD-GITA, paragraph 1.16

- ↑ Harle, J. C. (1994). The art and architecture of the Indian Subcontinent. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press. p. 410. ISBN 0-300-06217-6.

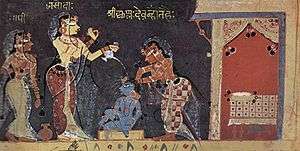

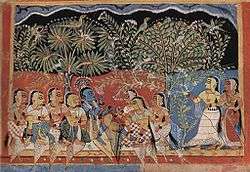

figure 327. Manaku, Radha's messenger describing Krishna standing with the cow-girls, gopi from Basohli.

- ↑ Hoiberg, Dale; Ramchandani, Indu (2000). Students' Britannica India. Popular Prakashan. p. 251. ISBN 9780852297605.

- ↑ Satsvarupa dasa Goswami (1998). "The Qualities of Sri Krsna". GNPress: 152 pages. ISBN 0-911233-64-4.

- 1 2 Vithoba is not only viewed as a form of Krishna. He is also by some considered that of Vishnu, Shiva and Gautama Buddha according to various traditions. See: Kelkar, Ashok R. (2001) [1992]. "Sri-Vitthal: Ek Mahasamanvay (Marathi) by R.C. Dhere". Encyclopaedia of Indian literature. 5. Sahitya Akademi. p. 4179. Retrieved 2008-09-20. and Mokashi, Digambar Balkrishna; Engblom, Philip C. (1987). Palkhi: a pilgrimage to Pandharpur — translated from the Marathi book Pālakhī by Philip C. Engblom. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 35. ISBN 0-88706-461-2.

- ↑ Stuart Cary Welch (1985). India: Art and Culture, 1300-1900. Metropolitan Museum of Art,. p. 58. ISBN 0030061148.

- ↑ Wendy Doniger (2008). "Britannica: Mahabharata". encyclopedia. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ↑ "Rig Veda: Rig-Veda Book 1: HYMN CLXIV. Viśvedevas". Sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 2012-06-02.

- ↑ Gaudiya scholar, Bhaktivinoda Thakura in his Dasa Mula Tattva Ch.3: 'Śrī Kṛṣṇa—The Supreme Absolute Truth', Part: Vedic Evidences of Śrī Kṛṣṇa 's Divinity

- ↑ Sunil Kumar Bhattacharya Krishna-cult in Indian Art. 1996 M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 81-7533-001-5 p. 126: "According to (D.R.Bhadarkar), the word Krishna referred to in the expression 'Krishna-drapsah' in the Rig- Veda, denotes the very same Krishna".

- 1 2 Archived 17 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Matapariksha: An examination of religions, Volume 1 By John Muir. Books.google.co.in. 1852. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ↑ The Religions of India Volume 1, Volume 1 By Edward Washburn Hopkins. Books.google.co.in. August 2008. ISBN 9780554343327. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ↑ Indian Hist (Opt) By Reddy. Books.google.co.in. 2006-12-01. ISBN 9780070635777. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- 1 2 Bryant 2007, p. 4

- ↑ Sunil Kumar Bhattacharya Krishna-cult in Indian Art. 1996 M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 81-7533-001-5 p.128: Satha-patha-brahmana and Aitareya-Aranyaka with reference to first chapter.

- 1 2 Hastings 2003, pp. 540–42

- ↑ Pâṇ. IV. 3. 98, Vâsudevârjunâbhyâm vun. See Bhandarkar, Vaishnavism and Śaivism, p. 3 and J.R.A.S. 1910, p. 168. Sûtra 95, just above, appears to point to bhakti, faith or devotion, felt for this Vâsudeva.

- ↑ Krishna: a sourcebook, pp 5, Edwin Francis Bryant, Oxford University Press US, 2007

- ↑ III. i. 23, Ulâro so Kaṇho isi ahosi

- ↑ Hemacandra Abhidhânacintâmani, Ed. Boehtlingk and Rien, p. 128, and Barnett's translation of the Antagada Dasāo, pp. 13-15 and 67-82.

- ↑ Bryant 2007, p. 5

- ↑ Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam, ed. India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 73.

- ↑ Barnett, Lionel David (1922). Hindu Gods and Heroes: Studies in the History of the Religion of India. J. Murray. p. 93.

- ↑ Puri, B.N. (1968). India in the Time of Patanjali. Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan.Page 51: The coins of Raj uvula have been recovered from the Sultanpur District.. the Brahmi inscription on the Mora stone slab, now in the Mathura Museum,

- ↑ Barnett, Lionel David (1922). Hindu Gods and Heroes: Studies in the History of the Religion of India. J. Murray. p. 92.

- ↑ Elkman, S.M.; Gosvami, J. (1986). Jiva Gosvamin's Tattvasandarbha: A Study on the Philosophical and Sectarian Development of the Gaudiya Vaisnava Movement. Motilal Banarsidass.

- ↑ Christopher Hitchens, God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything (Paperback), 2007, p. 23

- ↑ Chapman Cohen, Essays in Freethinking, 1927, "Monism and Religion"

- ↑ "Peter Joseph, Zeitgeist: The Movie, 2007". Vimeo.com. 2010-07-29. Retrieved 2013-04-03.

- ↑ "Gokulashtami". INDIA SUTRA.

- ↑ "Yashoda and Krishna". Metmuseum.org. 2011-10-10. Archived from the original on 13 October 2008. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ↑ Sanghi, Ashwin (2012). The Krishna key. Chennai: Westland. p. Key7. ISBN 9789381626689. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ Lok Nath Soni (2000). The Cattle and the Stick: An Ethnographic Profile of the Raut of Chhattisgarh. Anthropological Survey of India, Government of India, Ministry of Tourism and Culture, Department of Culture, Delhi: Anthropological Survey of India, Government of India, Ministry of Tourism and Culture, Department of Culture, 2000 Original from the University of Michigan. p. 16. ISBN 978-8185579573.

- ↑ Gopal Chowdhary (2014). The Greatest Farce of History. Partridge Publishing. p. 119. ISBN 978-1482819250.

- ↑ Bryant 2007, pp. 124–130,224

- ↑ Pargiter, F.E. (1972) [1922]. Ancient Indian Historical Tradition, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, pp.105-107.

- ↑ According to the Bhagavata and Vishnu Puranas, but in some Puranas like Devi-Bhagavata-Purana, her paternal uncle. See the Vishnu-Purana Book V Chapter 1, translated by H. H. Wilson, (1840), the Srimad Bhagavatam, translated by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, (1988) copyright Bhaktivedanta Book Trust

- ↑ Tripurari, Swami, Gopastami, Sanga, 1999.

- ↑ Lynne Gibson (1844). Calcutta Review. India: University of Calcutta Dept. of English. p. 119.

- ↑ Lynne Gibson (1999). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions. Merriam-Webster. p. 503.

- ↑ The English Writings of Rabindranath Tagore (ed. Sisir Kumar Das) (1996). A Vision of Indias History. Sahitya Akademi: Sahitya Akademi. p. 444. ISBN 81-260-0094-5.

- ↑ Schweig, G.M. (2005). Dance of divine love: The Rasa Lila of Krishna from the Bhagavata Purana, India's classic sacred love story. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ; Oxford. ISBN 0-691-11446-3.

- ↑ Largen, Kristin Johnston. " God at Play: Seeing God Through the Lens of the Young Krishna". Wiley-Blackwell. 1 September 2011. p. 256.

- ↑ Largen, Kristin Johnston. " God at Play: Seeing God Through the Lens of the Young Krishna". Wiley-Blackwell. 1 September 2011. p. 255.

- ↑ Largen, Kristin Johnston. " God at Play: Seeing God Through the Lens of the Young Krishna". Wiley-Blackwell. 1 September 2011. p. 253-261.

- ↑ "Krishna Rajamannar with His Wives, Rukmini and Satyabhama, and His Mount, Garuda | LACMA Collections". collections.lacma.org. Retrieved 2014-09-23.

- ↑ Bryant 2007, p. 290

- ↑ Bryant 2007, pp. 28–29

- ↑ Bryant 2007, p. 152

- ↑ Aparna Chatterjee (10 December 2007). "The Ashta-Bharyas". American Chronicle. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ↑ Charudeva Shastri, Suniti Kumar Chatterji (1974) Charudeva Shastri Felicitation Volume, p. 449

- ↑ David L. Haberman, (2003) Motilal Banarsidass, The Bhaktirasamrtasindhu of Rupa Gosvamin, p. 155, ISBN 81-208-1861-X

- ↑ Bryant 2007, pp. 130–133

- ↑ Rosen 2006, p. 136

- ↑ "Krishna & Shishupal". Mantraonnet.com. 2007-06-19. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ↑ Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita, by Robert N. Minor in Bryant 2007, pp. 77–79

- ↑ "Festival in honour of Chrishna". The Wesleyan Juvenile Offering: A Miscellany of Missionary Information for Young Persons. Wesleyan Missionary Society. X: 114. October 1853. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ↑ "Pradyumna, 5 Definition(s)". Wisdom.

- ↑ Bryant 2007, pp. 148

- ↑ Kisari Mohan Ganguli (2006). "The Mahabharata (originally published between 1883 and 1896)". book. Sacred Texts. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ↑ Mani, Vettam (1975). Puranic Encyclopaedia: A Comprehensive Dictionary With Special Reference to the Epic and Puranic Literature. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 429. ISBN 0-8426-0822-2.

- ↑ "Bhagvata Purana".

- ↑ "Srimad Bhagavatam :: Conto 11 - The Ascension of Lord Krishna". bhagavatam.in. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ↑ "Bhalka Tirth". Somnath Trust. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ↑ "Gujarat Tourism". Gujarat Tourism. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ↑ The Bhagavata Purana (1.18.6), Vishnu Purana (5.38.8), and Brahma Purana (212.8), the day Krishna left the earth was the day that the Dvapara Yuga ended and the Kali Yuga began.

- ↑ See: Matchett, Freda, "The Puranas", p 139 and Yano, Michio, "Calendar, astrology and astronomy" in Flood, Gavin (Ed) (2003). Blackwell companion to Hinduism. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-21535-2.

- ↑ Sutton (2000) pp. 174–175

- ↑ Kisari Mohan Ganguli (2006). "The Mahabharata, Book 5: Udyoga Parva: Bhagwat Yana Parva: section CXXXI (originally published between 1883 and 1896)". book. Sacred Texts. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ↑ Kisari Mohan Ganguli (2006). "The Mahabharata, Book 5: Udyoga Parva: Bhagwat Yana Parva: section CXXX(originally published between 1883 and 1896)". book. Sacred Texts. Retrieved 2008-10-13. "Knowest thou not sinless Govinda, of terrible prowess and incapable of deterioration?"

- ↑ Knott, Kim (2000). Hinduism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 160. ISBN 0-19-285387-2.

- ↑ "Information on Lord Krishna Birth and Death Time". Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ↑ "Journal Academic Marketing Mysticism Online (JAMMO). Vol 2. Part 6. 81-92. 21 August 2011". Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ↑ Dr Narhari Achar

- ↑ "The Scientific Timeline of Lord Krishna". Stephen Knapp.com.

- ↑ "Notable Horoscopes Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1991, ISBN 8120809009,9788120809000". Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ↑ "Krishna's Birth Chart". Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ↑ Sangave 2001, p. 104.

- ↑ Zimmer 1953, p. 226.

- ↑ Zimmer 1953, p. 183.

- ↑ "Lord Krishna lived for 125 years. In The Times of India article, September 8, 2004.". Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ↑ John Dowson (2003). Classical Dictionary of Hindu Mythology and Religion, Geography, History and Literature. Kessinger Publishing. p. 361. ISBN 0-7661-7589-8.

- ↑ See Beck, Guy, "Introduction" in Beck 2005, pp. 1–18

- ↑ Knott 2000, p. 55

- ↑ Flood (1996) p. 117

- 1 2 See McDaniel, June, "Folk Vaishnavism and Ṭhākur Pañcāyat: Life and status among village Krishna statues" in Beck 2005, p. 39

- 1 2 Kennedy, M.T. (1925). The Chaitanya Movement: A Study of the Vaishnavism of Bengal. H. Milford, Oxford university press.

- ↑ K. Klostermaier (1997). The Charles Strong Trust Lectures, 1972-1984. Crotty, Robert B. Brill Academic Pub. p. 109. ISBN 90-04-07863-0.

For his worshippers he is not an avatara in the usual sense, but Svayam Bhagavan, the Lord himself.

- ↑ Delmonico, N., The History Of Indic Monotheism And Modern Chaitanya Vaishnavism in Ekstrand 2004

- ↑ De, S.K. (1960). Bengal's contribution to Sanskrit literature & studies in Bengal Vaisnavism. KL Mukhopadhyaya.p. 113: "The Bengal School identifies the Bhagavat with Krishna depicted in the Shrimad-Bhagavata and presents him as its highest personal God."

- ↑ Bryant 2007, p. 381

- ↑ "Vaishnava". encyclopedia. Division of Religion and Philosophy University of Cumbria. Retrieved 2008-10-13. [Vaishnava] University of Cumbria website Retrieved on 5-21-2008

- ↑ Graham M. Schweig (2005). Dance of Divine Love: The Rڄasa Lڄilڄa of Krishna from the Bhڄagavata Purڄa. na, India's classic sacred love story. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. Front Matter. ISBN 0-691-11446-3.

- ↑ Bhattacharya, Gouriswar: Vanamala of Vasudeva-Krsna-Visnu and Sankarsana-Balarama. In: Vanamala. Festschrift A.J. Gail. Serta Adalberto Joanni Gail LXV. diem natalem celebranti ab amicis collegis discipulis dedicata.

- ↑ Klostermaier, Klaus K. (2005). A Survey of Hinduism. State University of New York Press; 3 edition. p. 206. ISBN 0-7914-7081-4.

Present day Krishna worship is an amalgam of various elements. According to historical testimonies Krishna-Vasudeva worship already flourished in and around Mathura several centuries before Christ. A second important element is the cult of Krishna Govinda. Still later is the worship of Bala-Krishna, the Child Krishna—a quite prominent feature of modern Krishnaism. The last element seems to have been Krishna Gopijanavallabha, Krishna the lover of the Gopis, among whom Radha occupies a special position. In some books Krishna is presented as the founder and first teacher of the Bhagavata religion.

- ↑ Basham, A. L. "Review:Krishna: Myths, Rites, and Attitudes. by Milton Singer; Daniel H. H. Ingalls, The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 27, No. 3 (May, 1968 ), pp. 667-670". 27. www.jstor.org: 667–670. JSTOR 2051211.

- ↑ Singh, R.R. (2007). Bhakti And Philosophy. Lexington Books. ISBN 0-7391-1424-7.

- p. 10: "[Panini's] term Vāsudevaka, explained by the second century B.C commentator Patanjali, as referring to "the follower of Vasudeva, God of gods."

- ↑ Couture, André (2006). "The emergence of a group of four characters (Vasudeva, Samkarsana, Pradyumna, and Aniruddha) in the Harivamsa: points for consideration". Journal of Indian Philosophy. 34 (6): 571–585. doi:10.1007/s10781-006-9009-x.

- 1 2 Klostermaier, K. (1974). "The Bhaktirasamrtasindhubindu of Visvanatha Cakravartin". Journal of the American Oriental Society. American Oriental Society. 94 (1): 96–107. doi:10.2307/599733. JSTOR 599733.

- ↑ Vaudeville, C. (1962). "Evolution of Love-Symbolism in Bhagavatism". Journal of the American Oriental Society. American Oriental Society. 82 (1): 31–40. doi:10.2307/595976. JSTOR 595976.

- ↑ Bowen, Paul (1998). Themes and issues in Hinduism. London: Cassell. pp. 64–65. ISBN 0-304-33851-6.

- ↑ Radhakrisnasarma, C. (1975). Landmarks in Telugu Literature: A Short Survey of Telugu Literature. Lakshminarayana Granthamala.

- ↑ Sisir Kumar Das (2005). A History of Indian Literature, 500-1399: From Courtly to the Popular. Sahitya Akademi. p. 49. ISBN 81-260-2171-3.

- ↑ Schomer & McLeod (1987), pp. 1-2

- ↑ Srila Prabhupada - He Built a House in which the whole world can live in peace, Satsvarupa dasa Goswami, Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1984, ISBN 0-89213-133-0 page xv

- ↑ Dwyer, G. (2010). Krishna prasadam: the transformative power of sanctified food in the Krishna Consciousness Movement. Religions Of South Asia, 4(1), 89-104. doi:10.1558/rosa.v4i1.89

- ↑ "Thiruppavai". Ibiblio. Retrieved 2013-05-24.

- ↑ Desika, Vedanta. "Gopala Vimshati". Ibiblio, Sripedia. Retrieved 2013-05-23.

- ↑ Varadpande p.231

- ↑ Varadpande p.232-3

- ↑ Zarrilli, P.B. (2000). Kathakali Dance-Drama: Where Gods and Demons Come to Play. Routledge. p. 246.

- ↑ Upinder Singh 2016, p. 26.

- ↑ See Jerome H. Bauer "Hero of Wonders, Hero in Deeds: "Vasudeva Krishna in Jaina Cosmohistory" in Beck 2005, pp. 167–169

- ↑ Jaini, P.S. (1993), Jaina Puranas: A Puranic Counter Tradition, ISBN 978-0-7914-1381-4

- ↑ Cort, J.E. (1993), An Overview of the Jaina Puranas, ISBN 9781438401362

- ↑ "Andhakavenhu Puttaa". www.vipassana.info. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- 1 2 Law, B.C. (1941). India as Described in Early Texts of Buddhism and Jainism. Luzac.

- ↑ Jaiswal, S. (1974). "Historical Evolution of the Ram Legend". Social Scientist. 21 (3-4): 89–97. JSTOR 3517633.

- ↑ Hiltebeitel, A. (1990). The Ritual of Battle: Krishna in the Mahabharata. State University of New York Press.

- ↑ The Turner of the Wheel. The Life of Sariputta, compiled and translated from the Pali texts by Nyanaponika Thera

- ↑ Guth, C.M.E. "Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 42, No. 1 (Spring, 1987 ), pp. 1-23". 42. www.jstor.org: 1–23. JSTOR 2385037.

- ↑ Smith, Peter (2000). "Manifestations of God". A concise encyclopedia of the Bahá'í Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. p. 231. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

- ↑ Esslemont, J.E. (1980). Bahá'u'lláh and the New Era (5th ed.). Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. p. 2. ISBN 0-87743-160-4.

- 1 2 Ahmad, Mirza Ghulam (2007). Lecture Sialkot (PDF). Tilford: Islam International Publications Ltd. ISBN 1-85372-917-5.

- ↑ "Krishna". Retrieved 2011-01-24.

- ↑ Revelation, Rationality, Knowledge & Truth. Ahmadiyya Muslim Community.

- ↑ Harvey, D. A. (2003). "Beyond Enlightenment: Occultism, Politics, and Culture in France from the Old Regime to the Fin-de-Siècle". The Historian. Blackwell Publishing. 65 (3): 665–694. doi:10.1111/1540-6563.00035.

- ↑ Schure, Edouard (1992). Great Initiates: A Study of the Secret History of Religions. Garber Communications. ISBN 0-89345-228-9.

- ↑ See for example: Hanegraaff, Wouter J. (1996). New Age Religion and Western Culture: Esotericism in the Mirror of Secular Thought. Brill Publishers. p. 390. ISBN 90-04-10696-0., Hammer, Olav (2004). Claiming Knowledge: Strategies of Epistemology from Theosophy to the New Age. Brill Publishers. pp. 62, 174. ISBN 90-04-13638-X., and Ellwood, Robert S. (1986). Theosophy: A Modern Expression of the Wisdom of the Ages. Quest Books. p. 139. ISBN 0-8356-0607-4.

- ↑ Crowley associated Krishna with Roman god Dionysus and Magickal formulae IAO, AUM and INRI. See Crowley, Aleister (1991). Liber Aleph. Weiser Books. p. 71. ISBN 0-87728-729-5. and Crowley, Aleister (1980). The Book of Lies. Red Wheels. pp. 24–25. ISBN 0-87728-516-0.

- ↑ Apiryon, Tau; Apiryon (1995). Mystery of Mystery: A Primer of Thelemic Ecclesiastical Gnosticism. Berkeley, CA: Red Flame. ISBN 0-9712376-1-1.

Sources

- Doniger, Wendy (1993), Purana Perennis: Reciprocity and Transformation in Hindu and Jaina Texts, SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-1381-0

- Sangave, Vilas Adinath (2001), Facets of Jainology: Selected Research Papers on Jain Society, Religion, and Culture, Mumbai: Popular Prakashan, ISBN 978-81-7154-839-2

- Singh, Upinder (2016), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Pearson Education, ISBN 978-93-325-6996-6

- Zimmer, Heinrich (1953) [April 1952], Campbell, Joseph, ed., Philosophies Of India, London, E.C. 4: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, ISBN 978-81-208-0739-6

Further reading

- Beck, Guy L. (1993). Sonic theology: Hinduism and sacred sound. Columbia, S.C: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 0-87249-855-7.

- Bryant, Edwin F. (2004). Krishna: the beautiful legend of God;. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-044799-7.

- Bryant, Edwin F. (2007). Krishna: A Sourcebook. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 0-19-514891-6.

- The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, translated by Kisari Mohan Ganguli, published between 1883 and 1896

- The Vishnu-Purana, translated by H. H. Wilson, (1840)

- The Srimad Bhagavatam, translated by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, (1988) copyright Bhaktivedanta Book Trust

- Knott, Kim (2000). Hinduism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 160. ISBN 0-19-285387-2.

- The Jataka or Stories of the Buddha's Former Births, edited by E. B. Cowell, (1895)

- Ekstrand, Maria (2004). Bryant, Edwin H., ed. The Hare Krishna movement: the postcharismatic fate of a religious transplant. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-12256-X.

- Gaurangapada, Swami. "Sixty-four qualities of Sri Krishna". Nitaaiveda. Nitaiiveda. Retrieved 2013-05-24.

- Goswami, S.D (1995). "The Qualities of Sri Krsna". GNPress. ISBN 0-911233-64-4.

- Garuda Pillar of Besnagar, Archaeological Survey of India, Annual Report (1908–1909). Calcutta: Superintendent of Government Printing, 1912, 129.

- Flood, G.D. (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43878-0.

- Beck, Guy L. (Ed.) (2005). Alternative Krishnas: Regional and Vernacular Variations on a Hindu Deity. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-6415-6.

- Rosen, Steven (2006). Essential Hinduism. New York: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-99006-0.

- Valpey, Kenneth R. (2006). Attending Kṛṣṇa's image: Caitanya Vaiṣṇava mūrti-sevā as devotional truth. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-38394-3.

- Sutton, Nicholas (2000). Religious doctrines in the Mahābhārata. Motilal Banarsidass Publ.,. p. 477. ISBN 81-208-1700-1.

- History of Indian Theatre By M. L. Varadpande. Chapter Theatre of Krishna, pp. 231–94. Published 1991, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 81-7017-278-0.

External links

- Krishna at Encyclopædia Britannica

- Iloveindia.com - Spirituality - Krishna