Ballard County, Kentucky

| Ballard County, Kentucky | |

|---|---|

Ballard County Courthouse in Wickliffe | |

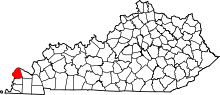

Location in the U.S. state of Kentucky | |

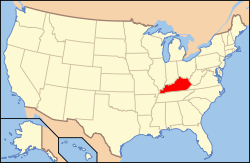

Kentucky's location in the U.S. | |

| Founded | 1842 |

| Named for | Bland Ballard |

| Seat | Wickliffe |

| Largest city | La Center |

| Area | |

| • Total | 274 sq mi (710 km2) |

| • Land | 247 sq mi (640 km2) |

| • Water | 27 sq mi (70 km2), 9.9% |

| Population | |

| • (2010) | 8,249 |

| • Density | 33/sq mi (13/km²) |

| Congressional district | 1st |

| Time zone | Central: UTC-6/-5 |

| Website |

www |

Ballard County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of the 2010 census, the population was 8,249.[1] Its county seat is Wickliffe.[2] The county was created by the Kentucky State Legislature in 1842 and is named for Captain Bland Ballard, a soldier, statesman, and member of the Kentucky General Assembly.[3] Ballard is a prohibition or dry county.

Ballard County is part of the Paducah, KY-IL Micropolitan Statistical Area.

History

Ballard County was formed from portions of Hickman County and McCracken County. It was named for Bland Ballard (1761–1853), a Kentucky pioneer and soldier who served as a scout for General George Rogers Clark during the American Revolutionary War, and later commanded a company during the War of 1812. On February 17, 1880, the courthouse was destroyed by a fire, which also destroyed most of the county's early records.[4] The county seat was transferred from Blandville to Wickliffe in 1882.[5]

Lynchings

Ballard County had documented incidents of racial violence in the 19th and early 20th century.

C.J. Miller

The journalist and civil rights leader Ida B. Wells, in her 1895 pamphlet A Red Record, details the gruesome death of C.J. Miller, an African-American traveling near Ballard County.[6]

On Wednesday, July 5, 1893, two girls, Mary and Ruby Ray, were found murdered outside their home near Wickliffe. Few clues were left except a blue coat at the crime scene. As news of the murders spread, search parties saw a white man hiding in a nearby cornfield. They fired at him, and he ran. A bloodhound picked up the scent, and tracked him to a ferry that ran between Wickliffe and Birds Point, Missouri. The ferry operator, Frank Gordon, told them he had just one passenger that evening, who had been either white or "a very bright mulatto." The bloodhound picked up the scent on the Missouri shore, but was not able track him inland.

The next day, C.J. Miller, an African-American traveler from Springfield, Illinois, had a verbal and physical altercation with a train brakeman at the Sikeston, Missouri train depot. Miller was arrested in Sikeston later that morning. Noticing that Miller was wearing a blue vest without a coat, they searched him and claimed they found rings inscribed with the first names of the murdered girls. The Sikeston town marshall telegraphed the sheriff of Ballard County. However, Miller protested his innocence, claiming he had never even been to Kentucky. Also, no such rings were presented as evidence.

Without waiting for an arrest warrant, the Ballard County sheriff chartered a train and with "a posse of thirty well-armed and determined Kentuckians" traveled to Sikeston to arrest Miller. On Friday morning, the sheriff brought Gordon to identify Miller as the man he had ferried to Missouri on the evening of the murders. Gordon told him that it was not the same man. The sheriff became angry and threatened Gordon with arrest on charges of complicity. Only then did Gordon say that Miller was the killer. Gordon and the search parties that spotted the murder suspect all described the him as being white. However, the Cairo Evening Telegram reported that Miller was "a dark brown skinned man, with kinky hair, 'neither yellow nor white.'" The Ballard County sheriff released Miller to the mob, who prepared to lynch him.

The father of the murdered girls strongly protested, knowing that their killer was a white man. Instead, an innocent man was about to be hanged, while the murderer walked free. Miller was taken to Ballard County, and on Friday, July 7, 1893, he made his final plea of innocence. Even as "numbers of rough, drunken men crowded into [Miller's] cell" to coerce a confession from Miller, he maintained his innocence, saying "burning and torture here lasts but a little while, but if I die with a lie on my soul, I shall be tortured forever. I am innocent." At 3:00 pm, a heavy log chain, weighing over one hundred pounds, was placed around Miller's neck, and he was dragged through the streets of the county seat and suspended from a telegraph pole. Miller was then raised with a stick and allowed to drop, breaking his neck. Members of the drunken crowd repeatedly fired into his body. Miller's lifeless body was left hanging for several hours. Then his fingers and toes were cut off as souvenirs and the body was burned in the streets.

Ida Wells wrote, "It is the honest and sober belief of many who witnessed the scene that an innocent man has been barbarously and shockingly put to death in the glare of the 19th century civilization, by those who profess to believe in Christianity, law and order."[7]

Tom Hall

On October 15, 1903, a mob organized near Wickliffe and the county jailer surrendered the keys to the Ballard County jail, to the mob. Tom Hall, a black man, accused of the critical wounding of a white man near Kevil on October 11, was lynched and left partially naked, suspended from a tree in Wickliffe.[8] Hall insisted he had no part in the shooting, which took place after a disagreement between two white men and a group of black men. Hall claimed he was an innocent bystander and was wounded by a stray shoot.[9]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 274 square miles (710 km2), of which 247 square miles (640 km2) is land and 27 square miles (70 km2) (9.9%) is water.[10]

State protected area

Axe Lake Swamp State Nature Preserve is a 458 acres (1.85 km2) nature preserve located in Ballard County, in the Barlow Bottoms. The preserve is part of the 3,000-acre (12 km2) Axe Lake Swamp wetlands complex which supports at least eight rare plant and animal species. The site has been recognized as a priority wetland in the North American Waterfowl Management Plan.[11]

Adjacent counties

- Pulaski County, Illinois (north) – across the Ohio River

- McCracken County (east)

- Carlisle County (south)

- Mississippi County, Missouri (southwest) – across the Mississippi River

- Alexander County, Illinois (west) – across the Ohio River

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 5,496 | — | |

| 1860 | 8,692 | 58.2% | |

| 1870 | 12,576 | 44.7% | |

| 1880 | 14,378 | 14.3% | |

| 1890 | 8,390 | −41.6% | |

| 1900 | 10,761 | 28.3% | |

| 1910 | 12,690 | 17.9% | |

| 1920 | 12,045 | −5.1% | |

| 1930 | 9,910 | −17.7% | |

| 1940 | 9,480 | −4.3% | |

| 1950 | 8,545 | −9.9% | |

| 1960 | 8,291 | −3.0% | |

| 1970 | 8,276 | −0.2% | |

| 1980 | 8,798 | 6.3% | |

| 1990 | 7,902 | −10.2% | |

| 2000 | 8,286 | 4.9% | |

| 2010 | 8,249 | −0.4% | |

| Est. 2015 | 8,212 | [12] | −0.4% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[13] 1790-1960[14] 1900-1990[15] 1990-2000[16] 2010-2013[1] | |||

As of the census[17] of 2000, there were 8,286 people, 3,395 households, and 2,413 families residing in the county. The population density was 33 per square mile (13/km2). There were 3,837 housing units at an average density of 15 per square mile (5.8/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 95.32% White, 2.87% Black or African American, 0.08% Native American, 0.18% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 0.08% from other races, and 1.44% from two or more races. 0.63% of the population were Hispanics or Latinos of any race.

There were 3,395 households out of which 30.70% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 59.60% were married couples living together, 8.00% had a female householder with no husband present, and 28.90% were non-families. 25.80% of all households were made up of individuals and 12.70% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.39 and the average family size was 2.85.

The age distribution was 23.10% under the age of 18, 7.60% from 18 to 24, 27.70% from 25 to 44, 25.40% from 45 to 64, and 16.20% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40 years. For every 100 females there were 97.50 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 94.00 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $32,130, and the median income for a family was $41,386. Males had a median income of $32,345 versus $20,902 for females. The per capita income for the county was $19,035. About 10.70% of families and 13.60% of the population were below the poverty line, including 19.30% of those under age 18 and 15.40% of those age 65 or over.

Politics

Voter Registration

| Ballard County Voter Registration & Party Enrollment as of November 17, 2015[18] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Political Party | Total Voters | Percentage | |||

| Democratic | 4,671 | 73.37% | |||

| Republican | 1,402 | 22.02% | |||

| Others | 227 | 3.57% | |||

| Independent | 57 | 0.90% | |||

| Libertarian | 5 | 0.08% | |||

| Green | 2 | 0.03% | |||

| Total | 6,366 | 100% | |||

Statewide Elections

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 67.96% 2,647 | 30.53% 1,189 | 1.51% 59 |

| 2008 | 62.49% 2,537 | 35.15% 1,427 | 2.36% 96 |

| 2004 | 57.19% 2,389 | 42.11% 1,759 | 0.70% 29 |

| 2000 | 48.38% 1,824 | 49.87% 1,880 | 1.75% 66 |

| 1996 | 28.43% 1,064 | 60.26% 2,255 | 11.31% 423 |

| 1992 | 28.56% 1,108 | 58.45% 2,268 | 12.99% 504 |

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 55.20% 1,312 | 41.65% 990 | 3.16% 75 |

| 2011 | 35.80% 773 | 59.01% 1,274 | 5.19% 112 |

| 2007 | 34.09% 927 | 65.91% 1,792 | 0.00% 0 |

| 2003 | 46.53% 1,433 | 53.47% 1,647 | 0.00% 0 |

| 1999 | 6.70% 99 | 83.28% 1,230 | 10.02% 148 |

| 1995 | 32.30% 938 | 67.46% 1,959 | 0.24% 7 |

Communities

Notable residents

Morris E. Crain, Medal of Honor recipient for his bravery during WWII.

Kenny Rollins, an American basketball player who was a member of the University of Kentucky's "Fab Five" who won the 1948 NCAA Championship, the 1948 Gold Medal Winning U.S. Olympic Team, and the NBA's Chicago Stags and Boston Celtics.

Oscar Turner (1825–1896), State Senator, U. S. Representative and namesake of Oscar, Kentucky.

See also

References

- 1 2 "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ http://www.kyenc.org/entry/b/BALLA02.html

- ↑ http://genealogytrails.com/ken/ballard/

- ↑ Hogan, Roseann Reinemuth (1992). Kentucky Ancestry: A Guide to Genealogical and Historical Research. Ancestry Publishing. p. 189. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ↑ Ida B. Wells-Barnett (1895). The Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States. pp. 46–49. ISBN 978-1-4429-4983-6.

- ↑ Ida B. Wells-Barnett (1 April 2014). On Lynchings. A Red Record. Courier Corporation. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-486-79364-1.

- ↑ "Tom Hall Was Taken From the Kevil Jail and Hanged". Pittsburgh Press. 1903-10-16. Retrieved 2015-05-15.

- ↑ http://nkaa.uky.edu/record.php?note_id=1534

- ↑ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- ↑ <Axe Lake Swamp State Nature Preserve web site URL accessed on 20 August 2006.

- ↑ "County Totals Dataset: Population, Population Change and Estimated Components of Population Change: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- ↑ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- ↑ "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- ↑ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 11, 2013. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-11-26. Retrieved 2014-11-28.

Coordinates: 37°04′N 89°00′W / 37.06°N 89.00°W